Abandon SPOTIFY Thievery

The $16.4-Billion Ship of Frauds and Smoke--and Extremely Ill-Sounding Streams--Can Be By Us Swiftly Sunk

Abandon SPOTIFY Thievery

Journalists LIZ PELLY and TED GIOIA have revealed recently how Spotify CEO DANIEL EK and the Company’s internally generated ‘Perfect Fit Content’ rob musicians of Streams and Millions of Dollars.

Feb. 14, 2024

Revealing the Robberies

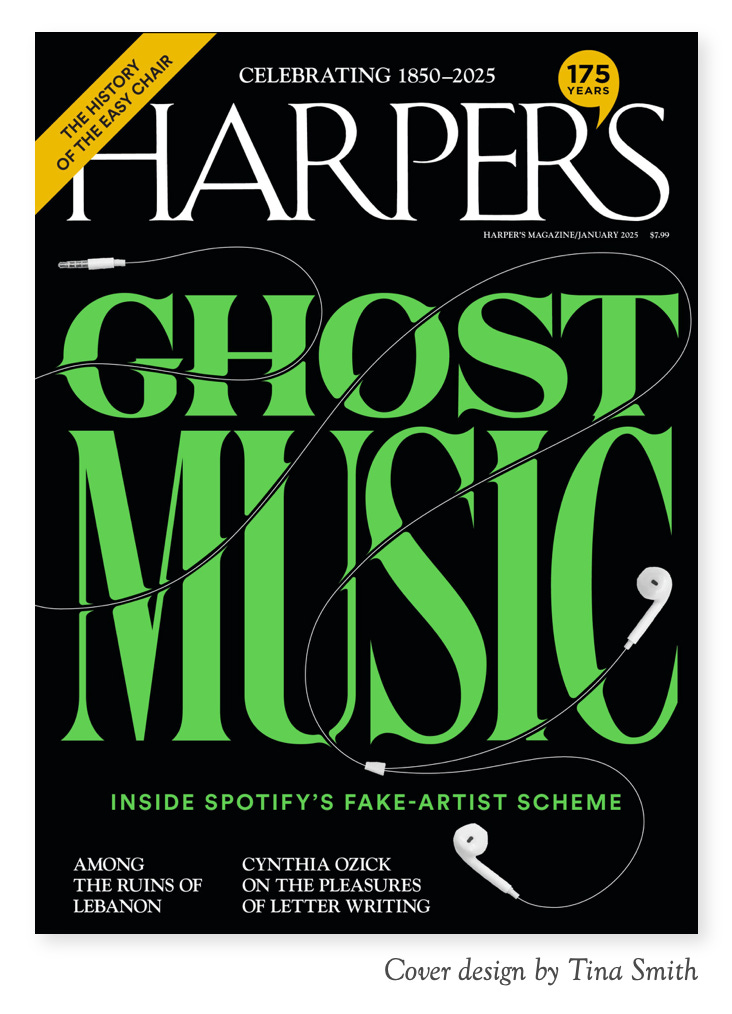

In December 2024 two journalists, LIZ PELLY and TED GIOIA, published articles about Spotify and Spotify’s use of a 10-member internal team to generate Tracks of ‘Perfect Fit Content’ in the Jazz and Ambient categories, put out under fake artists’ names, that in turn generated millions of Streams and lots of revenue. LIZ PELLY’s excerpt from her book Mood Machine appeared in Harper’s.

Ted Gioia picked up the baton from Pelly’s documentation of findings and suspicions that he’d raised since 2022.

Excesses of EK and Company

Years prior to the latest, welcome pieces of exposure, musicians had bemoaned how little was their share from Streams on the 21st-century’s leading Platforms.

Spotify was by multiples the least and worst.

Digital Music News writes on January 25, 2025,

‘Against the backdrop of price bumps – and an inherent streaming-volume increase – that refers to a global average of $3.41 per 1,000 streams in 2024, down just slightly from 2023’s $3.46 and more than that from 2022’s $3.69.

But behind the average, Amazon Music led the pack in royalties paid out per 1,000 streams ($8.80), followed by Apple Music ($6.20), YouTube ($4.80), and then Spotify ($3.00), the report shows.’

Let’s engage in a little ‘rithmetic. A little ‘rithmetic shows us that all four Platforms named—Apple Music and Amazon and Google’s YouTube and king Spotify— pay Artists/Labels less than one Penny per the Public’s Streaming of an artist’s work. Spotify cuts that Penny per Dollar into less than One/Third.

How small is One/Third of a Penny?

Better yet, how small in Ethics and Morality is the Corporation that pays artists less than One/Third of a Penny for a Dollar of revenue? Where does it rank among Dante’s Circles of Hell? Fits—and the word fits is used advisedly here—in about the seventh Circle, embodying both Greed and Fraud, we might reckon.

In Spotify that Corporation grew to a $16.4 Billion earner, with $1.191,205 Billion in Profit, for 2024.

Yes, Variety sang praises.

‘Spotify hit all the right notes in reporting Q4 and full-year 2024 earnings, with the audio streamer turning in its first annual net profit since it was founded in 2006.

Shares of Spotify surged more than 10% on the solid earnings report in early trading Tuesday.

For 2024, Spotify posted net income of €1.138 billion (versus a net loss of €505 million a year prior) on revenue of €15.673 billion, up 18.3%. The company gained 35 million total monthly average users in Q4 — its highest-ever fourth quarter net adds — to reach 675 million at year-end, and paid subscribers grew by 11 million (matching the record gain in Q4 2019) to hit 263 million.’

14 months earlier, December 2023, Spotify laid off 1500 workers despite what Fortume magazine termed ‘surprising growth’ in 2023.

So we may keep in mind the above-specified 1, 2. 3 of Facts about Spotify when we return to Ted Gioia’s and Liz Pelly’s revelations.

1. Spotify rewards musical artists with less than One/Third of a Penny per Stream. 2. Spotify’s revenue for 2024 totals more than $16.4 Billion and its Profit more than $1,191 Billion. 3. Spotify and Daniel Ek laid off 1500 workers, 14 months ago, December 2023, in the last month of ‘surprising growth’ during 2023.

We might even be prompted to fashion some Doggerel, a semi-Song of Spotify, for its Formula. “We pay so Little / And we’ve grown so Much / We know that Fewer People / And More A.I. will let us / Eat an even Bigger Lunch.”

‘Perfect Fit Content’ for Removing Humans from Music and Rewards

Back to Ted Gioia, the Honest Broker, and Liz Pelly and her illuminating how Spotify’s ‘Ghost Music’ works.

Ted Gioia wrote on December 19, 2024. (The boldng below is mine, meant to highlight some of the more flagrant deceits and excesses that Mr. Gioia presents for us.)

Ted Gioia as a young man from Hawthorne, California, elevating toward the rim.

‘In early 2022, I started noticing something strange in Spotify’s jazz playlists.

I listen to jazz every day, and pay close attention to new releases. But these Spotify playlists were filled with artists I’d never heard of before.

Who were they? Where did they come from? Did they even exist?

In April 2022, I finally felt justified in sharing my concerns with readers. So I published an article here called “The Fake Artists Problem Is Much Worse Than You Realize.”

[…]

Many of these artists live in Sweden—where Spotify has its headquarters. According to one source, a huge amount of streaming music originates from just 20 people, who operate under 500 different names.

Some of them were generating supersized numbers. An obscure Swedish jazz musician got more plays than most of the tracks on Jon Batiste’s We Are—which had just won the Grammy for Album of the Year (not just the best jazz album, but the best album in any genre).

How was that even possible?

[…]

A listener noticed that he kept hearing the same track over and over on Spotify. But when he checked the name of the song, it was always different. Even worse, these almost identical tracks were attributed to different artists and composers.

He created a playlist, and soon had 49 different versions of this song under various names. The titles sounded as if they had come out of a random text generator—almost as if the goal was to make them hard to remember.

[…]

Around this same time, I started hearing jazz piano playlists on Spotify that disturbed me. Every track sounded like it was played on the same instrument with the exact same touch and tone. Yet the names of the artists were all different.

Were these AI generated? Was Spotify doing this to avoid paying royalties to human musicians?

Spotify issued a statement in the face of these controversies. But I couldn’t find any denial that they were playing games with playlists in order to boost profits.

By total coincidence, Spotify’s profitability started to improve markedly around this time.

[…]

We now finally have the ugly truth on these fake artists—but no thanks to Spotify. Or to that prestigious newspaper whose editor I petitioned.

Instead journalist Liz Pelly has conducted an in-depth investigation, and published her findings in Harper’s—they are part of her forthcoming book Mood Machine: The Rise of Spotify and the Costs of the Perfect Playlist.

Mood Machine will show up in bookstores in January and may finally wake up the music industry to the dangers it faces.

[…]

Pelly kept pursuing this story for a year. She convinced former employees to reveal what they knew. She got her hands on internal documents. She read Slack messages from the company. And she slowly put the pieces together.

What I uncovered was an elaborate internal program. Spotify, I discovered, not only has partnerships with a web of production companies, which, as one former employee put it, provide Spotify with “music we benefited from financially,” but also a team of employees working to seed these tracks on playlists across the platform. In doing so, they are effectively working to grow the percentage of total streams of music that is cheaper for the platform.

In other words, Spotify has gone to war against musicians and record labels.

At Spotify they call this the “Perfect Fit Content” (PFC) program. Musicians who provide PFC tracks “must often give up control of certain royalty rights that, if a track becomes popular, could be highly lucrative.”

We shift now to Liz Pelly in Harper’s. January 2025.

Liz Pelly on Spotify’s Perfect Fit Content (and its Inevitable Acronym, PFC. Again, please indulge my bolding of some howlers and horrors.

[…]

‘What I uncovered was an elaborate internal program. Spotify, I discovered, not only has partnerships with a web of production companies, which, as one former employee put it, provide Spotify with “music we benefited from financially,” but also a team of employees working to seed these tracks on playlists across the platform. In doing so, they are effectively working to grow the percentage of total streams of music that is cheaper for the platform. The program’s name: Perfect Fit Content (PFC).

Like many other tech companies in the twenty-first century, Spotify spent its first decade claiming to disrupt an archaic industry, scaling up as quickly as possible, and attracting venture capitalists to an unproven business model. In its search for growth and profitability, Spotify reinvented itself repeatedly: as a social-networking platform in 2010, as an app marketplace in 2011, and by the end of 2012, as a hub for what it called “music for every moment,” supplying recommendations for specific moods, activities, and times of day. Spotify made its move into curation the next year, hiring a staff of editors to compile in-house playlists. In 2014, the company was increasing its investment in algorithmic personalization technology. This innovation was intended, as Spotify put it, to “level the playing field” for artists by minimizing the power of major labels, radio stations, and other old-school gatekeepers; in their place, it claimed, would be a system that simply rewarded tracks that streamed well. By the mid-2010s, the service was actively recasting itself as a neutral platform, a data-driven meritocracy that was rewriting the rules of the music business with its playlists and algorithms.

In reality, Spotify was subject to the outsized influence of the major-label oligopoly of Sony, Universal, and Warner, which together owned a 17 percent stake in the company when it launched. The companies, which controlled roughly 70 percent of the market for recorded music, held considerable negotiating power from the start. For these major labels, the rise of Spotify would soon pay off. By the mid-2010s, streaming had cemented itself as the most important source of revenue for the majors, which were raking in cash from Spotify’s millions of paying subscribers after more than a decade of declining revenue. But while Ek’s company was paying labels and publishers a lot of money—some 70 percent of its revenue—it had yet to turn a profit itself, something shareholders would soon demand. In theory, Spotify had any number of options: raising subscription rates, cutting costs by downsizing operations, or finding ways to attract new subscribers.

[…]

As a result, the thinking seemed to be: Why pay full-price royalties if users were only half listening? It was likely from this reasoning that the Perfect Fit Content program was created.

[…]

Eventually, it became clear internally that many of the playlist editors—whom Spotify had touted in the press as music lovers with encyclopedic knowledge—were uninterested in participating in the scheme. The company started to bring on editors who seemed less bothered by the PFC model.

[…]

By 2023, several hundred playlists were being monitored by the team responsible for PFC. Over 150 of these, including “Ambient Relaxation,” “Deep Focus,” “100% Lounge,” “Bossa Nova Dinner,” “Cocktail Jazz,” “Deep Sleep,” “Morning Stretch,” and “Detox,” were nearly entirely made up of PFC.

[…]

PFC eventually began to be handled by a small team called Strategic Programming, or StraP for short, which in 2023 had ten members. Though Spotify denies that it is trying to increase PFC’s streamshare, internal Slack messages show members of the StraP team analyzing quarter-by-quarter growth and discussing how to increase the number of PFC streams.

[…]

The roster of PFC providers discussed internally was long. For years, Firefly Entertainment and Epidemic Sound dominated media speculation about Spotify’s playlist practices. But internal messages revealed they were just two among at least a dozen PFC providers, including companies with names like Hush Hush LLC and Catfarm Music AB. There was Queenstreet Content AB, the production company of the Swedish pop songwriting duo Andreas Romdhane and Josef Svedlund, who were also behind another mood-music streaming operation, Audiowell, which partnered with megaproducer Max Martin (who has shaped the sound of global pop music since the Nineties) and private-equity firm Altor. In 2022, the Swedish press reported that Queenstreet was bringing in more than $10 million per year. Another provider was Industria Works, a subsidiary of which is Mood Works, a distributor whose website shows that it also streams tracks on Apple Music and Amazon Music. Spotify was perhaps not alone in promoting cheap stock music.

[…]

Perhaps Spotify understood the stakes—that when it removed real classical, jazz, and ambient artists from popular playlists and replaced them with low-budget stock muzak, it was steamrolling real music cultures, actual traditions within which artists were trying to make a living. Or perhaps the company was aware that this project to cheapen music contradicted so many of the ideals upon which its brand had been built. Spotify had long marketed itself as the ultimate platform for discovery—and who was going to get excited about “discovering” a bunch of stock music? Artists had been sold the idea that streaming was the ultimate meritocracy—that the best would rise to the top because users voted by listening. But the PFC program undermined all this. PFC was not the only way in which Spotify deliberately and covertly manipulated programming to favor content that improved its margins, but it was the most immediately galling. Nor was the problem simply a matter of “authenticity” in music. It was a matter of survival for actual artists, of musicians having the ability to earn a living on one of the largest platforms for music. PFC was irrefutable proof that Spotify rigged its system against musicians who knew their worth.

[…]

PFC is in some ways similar to production music, audio made in bulk on a work-for-hire basis, which is often fully owned by production companies that make it easily available to license for ads, in-store soundtracks, film scores, and the like.

[…]

Production music is booming today thanks to a digital environment in which a growing share of internet traffic comes from video and audio.

[…]

Companies like Epidemic Sound purport to solve this problem, claiming to simplify sync licensing by offering a library of pre-cleared, royalty-free production music for a monthly or yearly subscription fee. They also provide in-store music for retail outlets, in the tradition of muzak.

[…]

Unsurprisingly, one of the first venture-capital firms to invest in Spotify, Creandum, also invested early in Epidemic. In 2021, Epidemic raised $450 million from Blackstone Growth and EQT Growth, increasing the company’s valuation to $1.4 billion. It is striking, even now, that these venture capitalists saw so much potential for profit in background music. “This is, at the end of the day, a data business,” the global head of Blackstone Growth said at the time.

[…]

The Spotify–Epidemic corporate synergies reflect how streaming has flattened differences across music. The industry has contributed to a massive wave of consolidation: different music-adjacent industries and ecosystems that previously operated in isolation all suddenly depend on royalties from the same platforms.

[…]

In claiming to “simplify” the mechanics of the background-music industry, Epidemic and its peers have championed a system of flat-fee buyouts. The Epidemic composer I spoke with said that his payments were routinely around $1,700, and that the tracks were purchased by Epidemic as a complete buyout. “They own the master,” he told me. Epidemic’s selling point is that the music is royalty-free for its own subscribers, but it does collect royalties from streaming services; these it splits with artists fifty-fifty. But in the case of the musician I spoke with, the streaming royalty checks from tracks produced for Epidemic Sound were smaller than those for his non-Epidemic tracks, and artists are not entitled to certain other royalties: to refine its exploitative model, Epidemic does not work with artists who belong to performance-rights organizations, [Repeat from DP: Epidemic does not work with artists who belong to performance-rights organizations !!!] the groups that collect royalties for songwriters when their compositions are played on TV or radio, online, or even in public. “It’s essentially a race to the bottom,” the production-music composer Mat Andasun told me.

[…]

A model in which the imperative is simply to keep listeners around, whether they’re paying attention or not, distorts our very understanding of music’s purpose. This treatment of music as nothing but background sounds—as interchangeable tracks of generic, vibe-tagged playlist fodder—is at the heart of how music has been devalued in the streaming era. It is in the financial interest of streaming services to discourage a critical audio culture among users, to continue eroding connections between artists and listeners, so as to more easily slip discounted stock music through the cracks, improving their profit margins in the process. It’s not hard to imagine a future in which the continued fraying of these connections erodes the role of the artist altogether, laying the groundwork for users to accept music made using generative-AI software.

“I’m sure it’s something that AI could do now, which is kind of scary,” one of the former Spotify playlist editors told me, referring to the potential for AI tools to pump out audio much like the PFC tracks. The PFC partner companies themselves understand this. According to Epidemic Sound’s own public-facing materials, the company already plans to allow its music writers to use AI tools to generate tracks. In its 2023 annual report, Epidemic explained that its ownership of the world’s largest catalogue of “restriction-free” tracks made it “one of the best-positioned” companies to allow creators to harness “AI’s capabilities.” Even as it promoted the role that AI would play in its business, Epidemic emphasized the human nature of its approach. “Our promise to our artists is that technology will never replace them,” read a post on Epidemic’s corporate blog. But the ceaseless churn of quickly generated ghost-artist tracks already seems poised to do just that.

Spotify, for its part, has been open about its willingness to allow AI music on the platform. During a 2023 conference call, Daniel Ek noted that the boom in AI-generated content could be “great culturally” and allow Spotify to “grow engagement and revenue.” That’s an unsurprising position for a company that has long prided itself on its machine-learning systems, which power many of its recommendations, and has framed its product evolution as a story of AI transformation. These automated recommendations are, in part, how Spotify was able to usher in another of its most contentious cost-saving initiatives: Discovery Mode, its payola-like program whereby artists accept a lower royalty rate in exchange for algorithmic promotion. Like the PFC program, tracks enrolled in Discovery Mode are unmarked on Spotify; both schemes allow the service to push discount content to users without their knowledge. Discovery Mode has drawn scrutiny from artists, organizers, and lawmakers, which highlights another reason the company may ultimately prefer the details of its ghost-artist program to remain obscure. After all, protests for higher royalty rates can’t happen if playlists are filled with artists who remain in the shadows.’

We return to TED GIOIA on Spotify and its CEO, DANIEL EK.

On December 19, 2024 Ted Gioia compared Spotify’s deceptions with late-1950’s ‘Payola Scandals’—and found ‘Payola’ to be miniscule—like a Peanut to a Pyramid—in relation to Daniel Ek and his Company’s and Partners’ gains.

Ted Gioia wrote. (Again let me bold.)

‘They called it payola in the 1950s. The public learned that radio deejays picked songs for airplay based on cash kickbacks, not musical merit.;

[…]

‘Transactions nowadays are handled more delicately—and seemingly in full compliance with the laws. Nobody gives Spotify execs an envelope filled with cash.

But this is better than payola:

On February 7, Spotify’s CEO sold 250K shares for $57.5 million.

On April 24, Spotify’s CEO sold 400K shares for $118.8 million.

On November 15, Spotify’s CEO sold 75K shares for $35.8 million.

On November 20, Spotify’s CEO sold 75K shares for $34.8 million.

On November 26, Spotify’s CEO sold 75K shares for $36.1 million.

On December 4, Spotify’s CEO sold 75K shares for $37 million.

On December 11, Spotify’s CEO sold 60K shares for $28.3 million.

Deejay Alan Freed couldn’t dream of such riches. In fact, nobody in the history of music has made more money than the CEO of Spotify.

Taylor Swift doesn’t earn that much. Even after fifty years of concertizing, Paul McCartney and Mick Jagger can’t match this kind of wealth.’

Let’s again do some quick ‘rithmetic. Ek of Spotify sold Shares in his Industry-funded-and-partnered ‘service’ seven times between February 7 and December 11, 2024. By my count, the CEO who had laid off 1500 employees in December 2023 accumulated $378.3 Million from his selling Shares over a 10-Months span.

As Ted Gioia remarks: Neither Taylor Swift, Mick Jagger, or Paul McCartnet have ever made money close to $378.3 Million in less than one year.

Ted Gioia continues. Again I’ll dare to bold.

‘Let’s turn to the bigger question: What do we do about this?

By all means, let’s name and shame the perpetrators. But we need more than that.

Congress should investigate ethical violations at music streaming businesses—just like they did with payola. Laws must be passed requiring full transparency. Even better, let’s prevent huge streaming platforms from promoting songs based on financial incentives.

I don’t do that as a critic. People sometimes try to offer me money for coverage, and I tell them off. It happened again this week, and I got upset. No honest person could take those payoffs.

Streaming platforms ought to have similar standards. And if they won’t do it voluntarily, legislators and courts should force their hand.

And let me express a futile wish that the major record labels will find a spine. They need to create an alternative—even if it requires an antitrust exemption from Congress (much like major league sports).

Our single best hope is a cooperative streaming platform owned by labels and musicians. Let’s reclaim music from the technocrats. They have not proven themselves worthy of our trust.

If the music industry ‘leaders’ haven’t figured that out by now—especially after the latest revelations—we are in bad shape indeed.’

Above, TED GIOIA talks with RICK BEATO about the NEED for CREATION by PEOPLE to save both MUSIC and HUMANITY’S FUTURE.

More Sweeping Changes to Address Wider Crimes

Let me add a few of more Sweeping Changes to Ted’s ‘single best hope.’

It’s that MUSICIANS and PUBLIC combine on ‘cooperative streaming platform’ that WE ALL OWN.

Let’s have a closing look at Daniel Ek, as summarized in wikipedia and in wikispooks.

Above, Ek in wikipedia.

The wikispooks website offers more on Ek’s connections to global actors. He attended the World Economic Forum’s Annual Meeting in 2011, one year before Spotify re-shaped itself, according to investigative journalist Liz Pelly, as ‘a hub for what it called “music for every moment,” supplying recommendations for specific moods, activities, and times of day […] and three years before the company increased ‘its investment in algorithmic personalization technology,’

He attended his first Bilderberg meeting in Madrid, Spain, this past June. Wtrh Daniel Ek there were: Berge Brende of the Bilderberg Steering Committee and now President of the WEF, and Albert Bourla of Pfizer, Mark Carney of Goldman Sachs, Bank of Canada, Bank of England, and Chatham House, Anatoly Chubais, Peter Thiel of WEF Strategic Partners PayPal and Palantir Technologioes. et cetera.

Wikispooks presents about Bilderberg 2024:

‘According to Heiko Schöning, the meeting decided on several things. All elections in NATO were moved forward in a coordinated way in order not to disturb a planned state of emergency in 2025, as happened in the UK, France, Australia, timed with the US Presidential election. The emergency would either be "medical" or a war situation.[5] He also said the meeting made the preparation for a war against Russia in the Nordic countries and the Baltic Sea area, a "new Karelian war" where Finland would be the front line.[6]’

So , you see, we have much to address apart from how receive music. Music is nonetheless still in itself our most open means for messaging and touching and advancing each other.

WE have much to do. WE, the Public, and our Creations are Infinitely More Powerful than any and all of the Few who exploit us.

How might a new Platform between Musicians and Public be built? How might it Work? How can We, the Public we gain Control of the Internet?

Looking forward to what’s already working and what can work for even more!

As Malcolm X / El Malik el Shabazz said in On Afro-American History: ‘ “We want your suggestions […] With all of the combined suggestions and combined talent and know-how, we do believe that we can devise a program that will shake the world. Frankly. that’s what we need to do—shake the world.” ‘

RELATED

The Run on " 'CHASE' ": Customers Abandon a Bank that Abuses its Public Everywhere

“ ‘CHASE’ “ the Big Rock “Underwater”: A Criminal with more than 5000 Branches and more than $1.3 Trillion in ‘Uninsured Deposits’

ROGER LEWIS turns 83! Four Tracks from and for the master-musician, ROGER LEWIS, of New Orleans, recorded 2021-2024.

Roger and Don, recording for the Album LOUISIANA STORIES at the Marigny Studio in New Orleans, April 15, 2024—photo by ace engineer and musician ADAM KEIL.

Shut Down the WEF If You Want Peace, Freedoms and Prosperity in 2024.

Jump like Happy Dolphins into Santa Klaus Schwab’s Lap, Spouting Algorithms and Lassos that Will Turn His Would-Be World Upside-Down … Jump into Our Fight against the World Economic Forum in 2024

Endnotes and Urls

1. https://www.honest-broker.com/p/the-ugly-truth-about-spotify-is-finally

2. https://harpers.org/archive/2025/01/the-ghosts-in-the-machine-liz-pelly-spotify-musicians/

3. https://lizpelly.info/book

3. https://www.digitalmusicnews.com/2025/01/24/apple-music-royalty-rate-spotify-study/

https://www.reddit.com/r/technews/comments/1cbz884/spotify_ceo_daniel_ek_surprised_at_negative/?rdt=57142

5. https://fortune.com/europe/2024/04/23/spotify-earnings-q1-ceo-daniel-eklaying-off-1500-spotify-employees-negatively-affected-streaming-giants-operations/

6. https://www.honest-broker.com/p/the-fake-artists-problem-is-much

7.https://en.wikipedia.org/Daniel_Ek

https://wikispooks.com/wiki/B%C3%B8rge_Brende

8. https://wikispooks.com/wiki/Anatoly_Chubais

9. https://wikispooks.com/wiki/Mark_Carney

10. https://wikispooks.com/wiki/Bono

11. https://wikispooks.com/wiki/Peter_Thiel