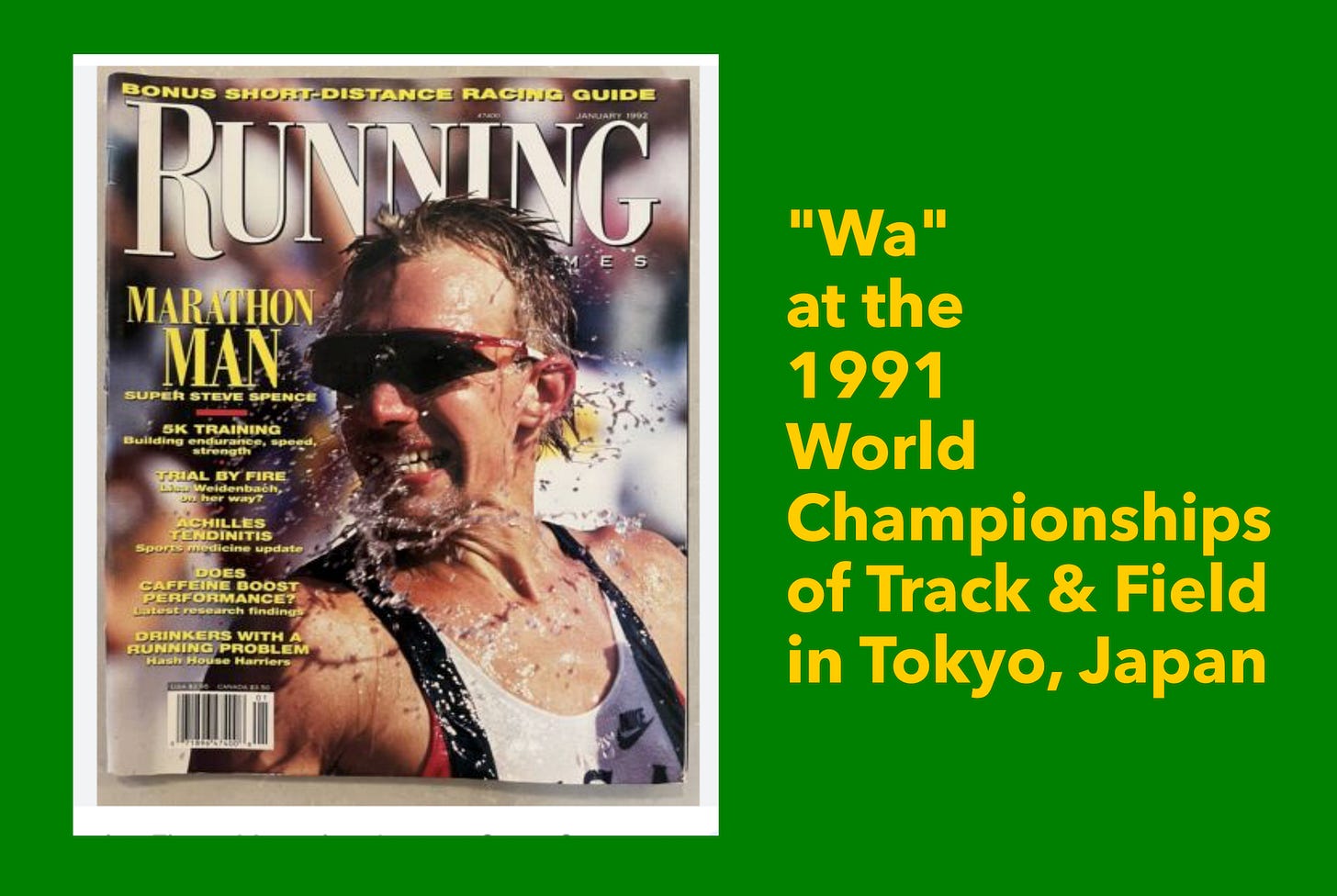

"Wa" at the Tokyo 1991 World Championships of Track & Field

Several Distance-Running Events at the 3rd of the "Greatest Track & Field Meets Ever".

In 1991 I wrote a piece for Running Times about distance-running events at that year’s World Championships of Track & Field. My subjects also were Tokyo and Japan.

Runners may benefit from the log of hot-weather training by medal-winner Steve Spence that's detailed by Amby Burfoot in Outside . Get very hot in training and sweat a lot and learn how to replenish yourself by running with a bottle of liquids. Run longer than your race's distance.

Jeff Benjamin in RunBlogRun talks with Steve about maintaining high volume of mileage in the final few weeks before a Marathon.

Other pieces about Steve’s training relate how he altered stride-length to succeed as a sub-marathoner and then shortened his stride to succeed as a marathoner. These pieces were in Running Times, but I can’t find them online. Cheers and happy-setting-of-your-own-records!

TOKYO 1991—

"WA" at the WORLD CHAMPIONSHIPS of TRACK & FIELD

Tokyo (“To-kee’yo, Japan,” Al Green pronounces it, responding warmly to his audience at a Concert there) is like a semi-tropical plant that's sustained in modernity through careful attentions.

Spread over more than 800 square kilometers, serving more than 11 million inhabitants, Tokyo, the capital of Japan, is made up of somehow nurturing contrasts. Giant cranes hoist steel beams for more skyscrapers--while broom-wielding men in orange uniforms and ducklike boots sweep leaves off the streets below these stalking cranes. Neon of corporate logos rears above Roppongi nightlife--while shops that sell seaweed are nestled like bouguets along bicycle-walks between boulevard-broad Doris.

For all its contrasts, Tokyo works. This city works most fundamentally, I’ve come to think after a few days here, because modern Japanese maintain attitudes of "Wa", the Shinto-bred belief, accepted to mollify centuries of ultimately disastrous and petrifying warfare, that society needs harmony.

Harmony in Japan includes secret relationships galore. Underworld Yakuza and madames in houses-of-pleasure with Bankers and Diet-members is one story that plays in the News of August 1991. Work-day to work-day, however, crowds flow and clock hours with an untroubled march. There can be, of course, 180-degree turns in such discipline. There can be explosive parades and willful, conscious, happy nonsense. Permeating everything, perhaps--source, perhaps, of pride, resentment and shame--is the abiding modern memory that Japan alone of Nations has suffered, then more than survived, holocausts from nuclear weaponry.

In August of 1991 Tokyo, the “To-kee’yo” that warmly embraces Soul such as Al Green's, is host to the third edition of the International Amateur Athletic Federation’s World Championships of Track & Field.

The 1983 and 1987 World Championships are often cited as the greatest Track-and-Field meets ever. The 1991 Championships promise to be superlative as well.

These Championships should fit Japan. They should let Japanese ahoqw their marriage of ritual and technology and their appreciation of performances that are both artful and courageous.

We journalists are ready. We watch from Media perches in the National Stadium. We have prime seats, rows of aeries with private headsets and screens, in this revered site. The National Stadium was scene for the most dynamic, engaging and breakthrough of Summer Olympics of the 20th Century, Tokyo 1964. High-definition TVs by our arm-rests afford us 10 channels of individual coverage of Events.

Cicadas whir in trees that surround the Stadium as the Championships’ flame trembles in its basin.

MEN'S 10,000 METERS,

MONDAY, AUGUST 25, 1991, START 20:10, 26• CELSIUS

The two Kenyan runners smile broadly after their win.

They, Moses Tanui and Richard Chelimo, have just finished 1st and 2nd in the 10,000 Meters Final this sultry Monday night. They sit with Mike Kosgei, Kenya's Coach for distance-running, behind microphones that are set along the platformed table of Media's Interview Room. They and we attending journalists are enclosed within four flat walls of this utilitarian Room that’s ground-level underneath spectators' seats in the Stadium.

Beside his rivals Khalid Skah of Morocco, 3rd Place, broods with his brows knit. Skah, who won the 1990 and 1991 World Cross-Country Championships with his devastating kick, has had his plans frustrated tonight by the Kenyan team's wildly taxing changes of pace.

"Three against one, it is not quite fair," Khalid Skah says.

Coach Mike Kosgei explains Kenya’s team-tactics. Richard Chelimo, only 19 and the 1991 world-leader at 10,000 meters with a 27:11.18 on June 23, was told to set a withering early tempo. Chelimo, his round face still cherubic, says: "My job was to go fast to block Skah." In laps varying from 61 to 67 seconds, the 19-year-old reached 3,000 meters in 8:01.79.

"If Skah follows, the World Record would fall," Kosgei says. "If he stays back, we would have a more controlled race. We have run against Skah in the Cross-Country Championships, and twice he has won in the end. We know that he can sprint well. We did not want to make it easy for him."

By the 8th lap Chelimo was some 40 meters ahead of Moses Tanui and some 60 meters ahead of Skah, Italian Salvatore Antibo, Englishman Richard Nerurkar and the Final's third Kenyan, Thomas Osano. As Tanui steadily advanced up the track on Chelimo (who passed 5000 meters in 13:30), Osano kept the trailing trio at least 8 seconds behind.

"Every time he was in front of me, he slowed down," Khalid Skah says. "It was very hard, because in the end I had to do all the work alone."

With 1200 meters to run Skah scooted past Osano. Starting the final lap 50 meters behind Tanui and Chelimo, he accelerated his low stride. Khalid Skah then looked like a rocket-sled intent on storming citadels. He made up all but 15 meters on the leading pair, his time 27:41.74 against Tanui’s 27:38.74 and Chelimo’s 27:39.41.

“But it was not enough to win,” Khalid Skah says.

WOMEN'S 10,000 METERS,

FRIDAY, AUGUST 30, 19:00, 27• C.

In Scotland Liz McColgan is known as "very tough-minded." Journalists from Great Britain say: "Liz is hard. Liz McColgan has got a strong will."

Liz McColgan led from the start of the Final of the Women's 10,000 Meters on Friday evening.

The ablest field since Seoul's 1988 Olympics--World-Record holder Ingrid Kristiansen of Norway and World Cross-Country Champion Lynn Jennings of the U. S. among them--filed behind the foward-tilting Scotswoman and her bobbing top-knot. Steamy heat again formed undulant waves in the air. Literally electric humidity boded the typhoon forecast for the next morning.

The lead women’s first lap was 71 seconds. 1600 meters passed in 4:54. McColgan pulled fellow British team-member Jill Hunter and two Ethiopans with her. Beyond the 3,000 meters-split of 9:16.96 only 19-year-old Derartu Tulu remained close.

The Event's question became whether Derartu Tulu could endure Liz McColgan's pressure. With 2500 meters to race McColgan surged, physically bending to her task, posture angled over her long legs. Tulu quickly fell a gap behind and then found her effort overtaken by two Chinese. Liz McColgan finished 21 seconds ahead of her nearest pursuers, the steady Chinese, Huandi Zhong and Xiuting Wang.

The tableau later with McColgan in athletes' and journalists' ground-level Interview Room is one of Queen and would-be Court. McColgan regards the reporters who are pressed before and beneath the platform where she sits with regal impatience. Back home in Britain tabloids in fact have betstowed on her the title ‘Queen Liz.’

"I moved by feel," the athlete answers about her surge away from Derartu Tulu. "I knew my fitness was very good, and I was willing to test anyone, " she says.

Another writer from England asks "Liz": Does she feel it had been "wise" to begin training so soon (ten days) after the birth of her first child (daughter Eilish) last November?

Liz McColgan looks at her fingernails.

"No," she answers. "As I've said, I don't feel any different. It has just made me more determined to prove that I'm the best."

WOMEN'S 1500 METERS,

SATURDAY, AUGUST 30, 19:00, 29• C.

"Yah! YAH! Yah-Yah--YAHHH!"

Thus--with exultant passion--with shouts from her gut to the sky above National Stadium--shouts that might arouse worshippers to their Mosque--22-year-old Hassiba Boulmerka of Algeria celebrates her joy just past the Finish-Line of the Women's 1500 Meters Final.

Hassiba Boulmerka has come a long way.

Five years ago the teen-ager was one of "about fourteen" women athletes in all of Algeria, she’s said. Inspired by Nawai El Moutawakil of the neighboring nation of Morocco (the 1984 Olympic gold-medalist at 400-meters hurdles), the fourteen or so Algerian aspirants had to disobey Islamic prohibitions that women must maintain in open, outdoor society their veiling yashmaks. The athletes were especially criticized for running bare-legged.

Hassiba Boulmerka stayed with her dream. She failed to advance from Heats in both the 800 and 1500 Meters in Seoul's 1988 Olympics, but repeated as African champion in those distances the following year. In 1990 she ranked 11th at 1500 Meters. This year she's broken through, with wins in her Event at two Grand Prix Meets in Europe, before coming to Tokyo.

The Women’s 1500 Meters Final on Saturday evening is run in a post-monsoon swelter. 66-second laps are led by Susan Sirma of Kenya. At the bell Sirma fronts Boulmerka, tall Olympic 800-meters champion Doina Melinte of Romania, powerful Tatyana Dorovskikh of Russia (a double Gold-medalist in Seoul’s 1988 Olympics), and PattiSue Plumer of the U. S.

Hassiba Boulmerka bolts into 1st at the end of the closing backstretch. She then flies as if shot from a spring into the finishing curve. Her arms pump like a lever-driven locomotive's. Down the home straight Dorovskikh chases the Algerian with a great lift. Boulmerka, however, maintains her form.

Across the Finish-line she throws up her arms.

Then she turns her face toward the sky. "Yah! YAH! Yah-Yah--YAHHH!"

Asked later if she'd shouted anything specific, Hassiba Boulmerka replies: "No. It was a cry of joy and release."

MEN'S 1500 METERS,

SUNDAY, SEPTEMBER 1, 15:40 31• C.

Training-partners of Noureddine Morcelli's in Riverside, California, where he went to Junior College, say that he could race at 400 meters internationally. He's run 46 in practice, they say. "It's scary how fast he is," they say.

Not since Herb Elliot of Australia between 1958 and 1960, Peter Snell of New Zealand in 1964, and Jim Ryun of the U. S. in 1966 and 1967, has any one runner been so dominant at the 1500 Meters/Mile distances as Morcelli is now. Other great record-setters of the past thirty years (Filbert Bayi of Tanzania and John Walker of New Zealand, Steve Ovett and Sebastian Coe and Steve Cram of the U.K., Steve Scott of the U.S., and Said Aouita of Morocco) all have had close rivals.

This year Said Aouita has come back. Aouita, holder of the 1500 Meters World Record at 3:29:46 and the greatest 1500-5000 Meters-runner of the 1980s, is racomg again after an operation to repair one of his hamstrings. The 32-year-old, fervently fierce as a competitor, poses a challenge to Morcelli. Aouita ran 3:33 in early August, a time with striking distance of his and Morcelli's best.

Pace in the Final is reasonable. Kenyan paratrooper David Kibet leads through 400 in 58.02, and his 800 meters is 1:58.43. Aouita stays close in lane 2. With a lap to go Morcelli surges into the lead.

The male Algerian’s stride is long, low and quick. His further pick-up. down the backstretch, is instantaneous as a whippet’s. He speeds through the final 400 in 51.55, 2 full seconds ahead of fellow 22-year-old Wilfred Kirochi of Kenya.

Noureddine Morcelli combines the ability to sprint with the fitness and form to set a withering pace. His mix is the new model for his event.

MEN'S MARATHON,

SUNDAY, SEPT. 1, 6:00 START, 26-30• C.

Hiromi Taniguchi still emits a glisten of sweat one hour after his short, swinging and ecstatically driven strides carried him to decisive victory in the Men’s Marathon. He explains to journalists in our Interview Room that he'd become a distance-runner in order to drink free orange-juice.

The Japanese champion has given us answers of unexpected thoroughness now more than 30 minutes into the session that began at 9:00 a.m., three hours after Start of the Marathon. He replies with careful politeness and mind-boggling detail. Translators occupy more minutes with their recounting of the athlete's responses.

Question for Mr. Taniguichi: Can he please us what inspired him to become a distance-runner?

Nodding with diligent attention, the 31-year-old begins his reply. A tale in Japanese unfolds. Taniguchi marks his frequent points of emphasis with vigorus nods. Perhaps 10 minutes--more than five, certainly--advance as the Silver and Bronze finishers in today’s Marathon, Ahmed Saleh of Djibouti and Steve Spence of the United States, observe and wait.

The Translator sets forth. "Mr. Taniguchi says: When he was a boy in school he watched the Fukuoka Marathon. He knew that this was a very famous Marathon in Japan. It happens every December.

He says: I saw that all the runners were able to drink from cups when they ran on the Fukuoka course. They could drink water or drink orange-juice. He thought that having this refreshment must be very pleasant ...

So that now, every day, thanks to his team and his coaches, Mr. Taniguchi is able to drink the delicious orange-juice. He is very glad for his teammates and coaches and his Company's support. He is able, thanks to this support, to train at such a level that today's result was possible."

Taniguchi nods once more to affirm his statements and adds a quick, closing smile.

Ahmed Saleh of Djibouti sits to the right of the Japanese winner. The north African at age 34 is himself many times a champion. Since 1985 Saleh has won the World Marathon Cup in 2:08:09 and placed 2nd in the 1987 World Championships and 3rd in the 1988 Olympics. Today he’s 2nd again, His cheekbones and limbs are angular like sun-browned bones. His stare straight ahead, as Taniguchi and Translators speak into their second half-hour, is as if some phenomenon as inexplicable as a Roc has landed and refused to move in front of him. Steve Spence, 3rd-Place, the Men's Marathon's great surprise, sips from a glass of water.

The race this morning was beautiful to watch in its unfolding. Runners showed the tremendous courage and tactical sense of all great athletes.

As dawn lifted into dripping mist just past 6:00 a. m., dozens in the Marathon peeled out of National Stadium to run more than 25 miles through “To-kee’yo.” Foremost among the favorites were 1988 Olympic champion Gelindo Bordin of Italy, Steve Moneghetti of Australia (1990's fastest marathoner with his 2:08:16 at Berlin), and Abebe Mekonnen of Ethiopia.

Heat quickly rose above 80 degrees F•. Humidity stuck near 100%. The city was more like hothouse than plant. Stephen Freigang of Germany and Steve Monighetti headed a pack of 12 more runners at 10-K in 31:08—about 5:00 per mile or 3:07 per kilometer, a rhythm would have finished in somewhere within 2:11 for the Marathon. By 15-K pace had slowed and Gelindo Bordin had brought five more into the dense, fronting pack.

Fumes blew into their faces from buses and cars that bore officials and photographers. Attrition was dramatic. Mekonnen, Pan-American Games winner Alfredo Cuba of Cuba, Freigang, Canada's Peter Maher, and more fell behind. At 25-k (1:18:57) both Steve Moneghetti and Japan's Takeyuki Nakayama blanched and lost contact.

Eight stayed together--Bordin and fellow Italian Salvatore Bettiol, Poland's Jan Huruk, Mexican Maurilio Castillo, Ethiopian Tekeye Gisilase, Ahmed Salah, and two Japanese, Futioshi Shinohara and Hiromi Taniguchi. At 33-k Bordin threw off his white cap. Steamy heat maintained its toll. Splits rose to 16:37 and 16:33 for the 5-k's between 25 and 35. This Marathon appeared to have only these eight left as possible victors.

Another runner came into view on our TV screens inside the Stadium. Intently drawing from the spout of his water-bottle, Steve Spence, U. S. record-holder at 15 kilometers in 42:40 but a relatively inexperienced, 2:12 marathoner, gained on the lead back up a boulevard-like Dori. This slope was the course's one significant long-climb, it ascending about 100 feet in 2 kilometers. Spence high strides looked like those of a knight’s charger.

Spence caught the lead pack at 37-k. Bordin and Bettiol glanced at him with shock.

"At that point I thought I might be able to win," Spence tells us in the Interview Room. "But it turned out that some guys were just hanging out."

That is, around 38K Hiromi Taniguchi veered right on the broad roadway and scooted ahead. He threw his rocker-arm-like strides into higher turnover. His head tilted more sideways and backward. Saleh and Shinohara gave chase. Taniguchi, however, was transported by the bravery of his move and its chance of triumph. Grimacing more, he drove on between crowds' flag-waving cheers. His eyes scrunched tighter His grimace grew wider in its etched plate. His stress was less of pain than it was of achieving victory and bliss.

He gained about 100 meters on Saleh.

Within the Marathon course’s sight of the Stadium, our TVs’ many-channeled coverage caught Spence's striding past Huruk and Shinohara. Once on the track, the runner from Pennsylvanie gained 6 more seconds more on Saleh in 500 meters, closing with 71-second 400. He became the first male marathoner from the U. S. to medal in a major international championship since Frank Shorter won Silver at the 1976 Olympics.

In the Interview Room reporters question Spence further. What does he think his accomplishment means for U.S. running?

"I think it was just a matter of time before one of us broke through," he says. "Fortunately for me I got to be the one."

Questions return to Taniguchi. He’s asked how he prepared in the day before the Marathon.

“You would like to know what time did Mr. Taniguchi go to sleep last night, and what did he have to eat?” begins the translated reply.

“He says: I had some pasta for supper. With it, some cheese. The cheese that you sprinkle. Parmesan? Yes, Parmesan. I also had bread and butter…. Last night at 7:40 I lay down on my bed. At first I could not sleep, but then I did…. At 2:00 a train went by outside. I know because I put my watch beside my bed. I woke up to look out my window. I wondered what time it was, and so I looked ... This morning, when it was still dark, I did have some breakfast, yes. My breakfast was toast with tea. At 4:30, as my coaches had planned, we got on the train to come to the Stadium.... "

Hiromi Taniguchi is asked what intentions he’d brought to this Marathon.

This question he answers in one sentence. His coach, 2:09-marathoner Takehishi Soh, nods in agreement next to his athlete.

The translator delivers to us: "Mr. Taniguchi says that he came to these Games with the belief that all his ability would be manifested."

CLOSING CEREMONY

SUNDAY, SEPTEMBER 1, 19:00 ..., 27 C•

Sunday evening's Closing Ceremony gathers national teams inside the Stadium. Beside the pixellated scoreboard and below the pot of quivering flames, Taiko drummers beat their rhythms dense and deep into crescendos, themselves ecstatic yet exact. Athletes march in lines across the green and lighted infield.

During the preceding week many winners have thanked those close to them for support. U. S. Decathalete Dan O'Brien said: “My coaches had me ready to perform on an asphalt track if that was necessary.”

Long-jumper Mike Powell, who broke the most enduring and awesome of Track & Field World Records in a duel with Carl Lewis that was this Championship’s most memorable contest, said: “I’ve seen myself break that Record for seven years. I’ve really got to thank my coach, Randy Huntington.”

Hassiba Boulmerka of Algeria and Steeplechase-winner Moses Kiptanui of Kenya also acknowledged that they’d succeeded through the help of peers.

That is, without naming “Wa” but perhaps feeling forms of “Wa” here in Japan, they’d drawn from "Wa" to achieve their individual excellence.

Ah yes, individual excellence from collective enterprise. Contrary to stereotypes of Japanese as lockstep salary-men and obedient wives, this millenia-old guide, "Wa", is NOT meant to produce unthinking conformity and passable mediocrity. Like other ancient wisdom, it allows room for opposites--for contrasts-- for REBELLION, even--in its whole.

On the concluding weekend of these Championships, folk dancing of Awa Dori took over streets in Koenji, nearby Shinjuku's neon-blazoned high-rises of Shops, Stores and Nightclubs.

One folk song there told the crowd: "Those who dance are fools! / And so are those who watch!"

Aboard trains of the shinily scrubbed and swiftly shuttlting Underground of Tokyo, I’ve seen every day and night people talking in genuinely interest and inquiring conversation. There are discussions and personalities, not the worn-out robotic, here.

Now, in the middle of the Closing Ceremony’s pre-set order, athletes who march on the Stadium's infield break ranks suddenl.

They come apart. They join together in new and spontaneous formations. They veer into multi-colored asymmetry below the TV screens on the armrests of our seats.

They diverge onto the National Stadium’s Track like streamers. They’re like cavorting dancers and then in fact become cavorting dancers. They throng and fling with arms on arms and hands aloft.

A voice tries to control them. Announcing for the Championships' organizer, the International Amateur Athletic Federation, a woman broadcaster from Italy, who has herself passionately conveyed dramas of these these past nine days, now requests: "All athletes will please stay on the field."

At once the Japanese team disobeys by trotting onto the Track. Still following their upraised flag of the Rising Sun, they go counter-clockwise. Athletes smile. Or athletes wave. Or athletes both smile and wave. They celebrate according to how they feel.

Yes, those chock-full days in Tokyo, Andy--on the track in the Stadium and elsewhere. A benign and elevated atmosphere. Appreciating you again!

Thanks Don. Fascinating.