The Boys from Bukoba

Oyster Bay.

Sunday afternoons On Sunday afternoons in Dar es Salaam I took a break from downtown. My second-floor room in the Hotel Zanzibar on Zanaki Street was of cement walls and floor and one 6o-watt bulb, the 8-by-10 foot dimensions of a large cell. Tropical August's languor seldom stirred muslin curtains of the room's single window. The window most admitted jukebox music from the bar--yes, it WAS called the Zanzibar Bar--below. You could sweat without moving. Buildings and shadows kept this version of Zanzibar from breeze off the Indian Ocean.

My Sunday afternoon jog and walk out to Oyster Bay was a reward for the week's work. Monday through Saturday and Sunday too, these months of Summer 1977, I rose with dawn and clumped down cement stairs in my Red Wing boots as vendors rolled our

their sisal mats on Zanaki Street. I prepared for another day's writing and less regular masturbating with a cup of coffee and a sambusa and a cigarette of pungently acrid Tanzanian tobacco in the Tea and Sandwich shop one block away. When I returned to

the Hotel Zanzibar's front, mounds of mangos, tomatoes, cabbages and onions, bunches of tiny-tasseled carrots, and snub-nosed, poppy-yellow bananas were on display across the street. A banana and a carrot and a roll were my lunch. Ugali was the most usual dinner.

21st-century vendors in Dar es Salaam.

I'd come to Tanzania because--as the essay 'Once Up the Country of Ujamma' states--I felt it might be 'the brightest hope in the world.' A few months earlier, April of 1977, I'd watched with Gayl Jones in Ann Arbor, Michigan a documentary about building of the Tarzara Railway between Dar es Salaam and the capitol of Zambia, then named Lusaka, more than 1000 miles away. Laborers' energy with their picks and tie-tongs and their chants and songs and their post-work and pre-work exuberance and enthusiasm over meals and tea impressed me mightily. "There's a lot of spirit there," I said to Gayl.

Construction of the Railway is described on the website maintained by China's Embassy in Tanzania's capital, the interior city of Dodoma.

‘Running some 1,870 km (1,160 mi) from Dar es Salaam to Zambia's Kapiri Mposhi, the railway took only five years to build and was finished ahead of schedule in 1975. Before the railway construction began, 12 Chinese surveyors travelled for nine months on foot from Dar es Salaam to Mbeya in the Southern Highlands to choose and align the railway's path. Thereafter, about 50,000 Tanzanians and 25,000 Chinese were engaged to construct the historical railway.

Braving rain, sun and wind, the workers successfully laid the track through some of Africa's most rugged landscape. The work involved moving 330,000 tonnes of steel rail and the construction of 300 bridges, 23 tunnels and 147 stations. The bridge across the Mpanga River towered 160 feet (49 m) in height, and the Irangi Number Tunnel tunnel was one half-mile 0.8 km) long.’

Tarzara Railway bridge.

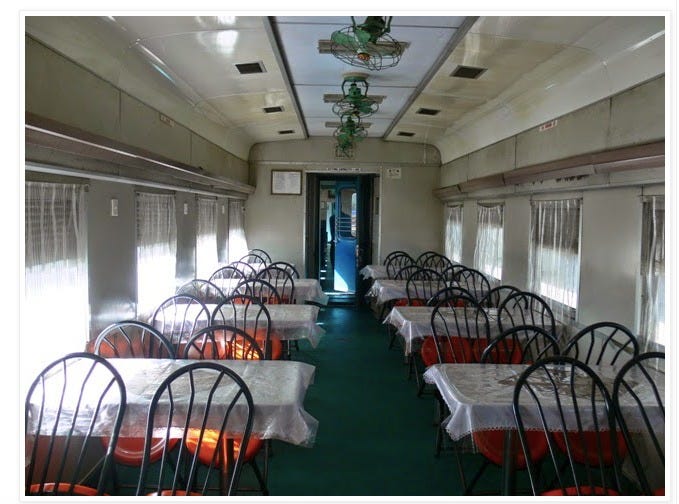

Tarzara Railway dining-car.

Subsequently I dipped into books of essays by Tanzania's President, Julius Nyerere, Freedom and Unity (Uhuru na Umoja) and Freedom and Socialism (Uhuru na Ujama) and tried to read Nyerere's Kiswahili translation of Shakespeare's Julius Caesar. Previously I'd known Tanzania from Cuba's and Che Guevara's campaign in the Congo of 1965 and from my Stanford Creative Writing Program friend and classmate Hunt Hawkins and Hunt's year as a teacher in Dar.

I'd landed one morning in mid-July after flights from London and Zurich. My first amazement in the glaring sunlight were files of brightly berobed women bearing baskets on their heads along the road to Dar from the Airport. Their robes, I learned, were called khangas or kitenges and the goods on their heads were their and their families' livelihoods. Soon after finding cheap lodging (the Zanaki) I wrote the poem 'Over Dinner' that I recorded with Henry Kaiser in the same year, 1991, that Henry and David Lindley recorded with superlative musicians in Madagascar their A World Out Of Time albums. I awaited word from the Government about my applications to interview Nyerere and to become a schoolteacher.

Mornings in the Hotel Zanzibar I passed Rashid behind his Reception counter. Rashid was Manager of this part of his family's business. He was in his 20s like me and his hair was jet-black and his smile was like his mind: quick. Early in my stay a shy knock had tapped on my cement-floored room's door. Outside stood one of the slender

"debs" from the Bar downstairs.

"Hello," I said.

"Rashid sent me," she said in English that tentatively handled each syllable. "Would you like company?" she asked.

"Uh, well," I said, "no. No, but thank you. And please thank Rashid." The next morning I related the exchange to Rashid and repeated my thanks.

"Ah, yeah. That is no problem, Don. I understand. I used to go with the debs, but then I got disease."

Rashid later fitted a metal coaster-table and a three-shelf bookcase into my room. The chair too was special, as it had a cushion and a straight wooden back. "A writer must have the proper furniture," Rashid said.

Wherever the hotel room in my traveling 1970s, I practiced a set routine. After first cigarette and coffee I wrote till noontime, then had a small lunch, then wrote till at least mid-afternoon. In Dar my projects were all non-fiction. I typed pages on the azure-blue Royal portable that's I'd carried since 1968, driving or hitchhiking across North America. Or I wrote longhand in the ringed notebooks that were likewise longtime companions, my worn-cornered American Heritage Dictionary and Roget's Thesaurus at hand. The discipline protracted concentration over hours. I had two essays going. One recounted a trip north to Arusha and Ngorongoro that afforded sidelights into struggles of post-colonial east Africa--the aforesaid 'Once Up the Country of Ujamaa'. The second essay became 'Roll Away der Rock', a review of rock 'n' roll into Rock. Punk Rock was manifest by my catching the Ramones' drill in Ann Arbor, Michigan and smiling at passionately bouncing pogo-ers in London's Roxy Club.

earlier in 1977.

At night I plowed again into the reading and longhand notes that seemed essential for an essay that bestrode the lives and works of D.H. Lawrence and Thomas Mann. The latter essay, 'Lawrence and Mann Overarching', become book-length itself. Twice in the past 18 months I'd lost manuscripts of and for it that were both typed and longhand. The day after Christmas 1975--the day after I'd spent Christmas in Tijuana by Romantic design--someone stole the suitcase that had been beneath my bed in a Main Street flophouse of Los Angeles. January of this year, a second suitcase, containing a second 'Lawrence and Mann ...' manuscript and dozens of pages in longhand notes, disappeared forever from me in Grand Isle, Louisiana. The driver of a car who'd picked up me and a fellow hire hitch-hiking nearby Raceland, Louisiana, both of us scheduled to start as Roustabouts for Diamond M Drilling IF we could reach the dispatcher's office in Grand Isle by 9:00 p.m. for our crew-boat, ... that driver so fond of repeating the emphasis "Damn straight!", took off with our suitcases in the trunk of his car. All those footnotes were lost again!

Mid-afternoon of weekdays in Dar I looked forward to a swim beside the port-city's Harbor. These swims preceded in my stay the Sunday jog-and-walk to Oyster Bay. A rolled-up towel in one hand, khaki shorts under my slacks, I'd trot in my $19 running-shoes from the Zanzibar along dusty Streets and perilous Roundabouts, avoiding tourists' Avenues and the Hotel Kilimanjaro, to a beach of light-colored sand, past mouth of the Harbor, where fisherman landed their dhows of single sails.

It was great to hit the water. 'Ocean, I have loved thee'--such was always true for me. Stripping to shorts and bare feet and dashing down the hot sand into breakers that crested and lapped to shore. Diving deeper into the currents' cooling surges. Swimming underwater upside-down like an otter as far out as your breath allowed and your nerve dared. Swimming back and forth some hundreds of yards from the sometimes curious fishermen and their sons and never knowing what abrupt swell or pull or chill might invade and combat your exertions with powers far greater than yours. Almost any physical exercise pleases me; that which carries some risk is of course more elevating.

Oyster Bay was a bigger deal than swimming rather close to downtown Dar. Its main beach lay about two miles from the Zanzibar. I jogged most of the way, angling southeast away from two- and three-story buildings' shadows to the main Road for the coast--past the city's Golf Course--past Agip and BP gas-stations--to Oceanward streets named after Jomo Kenyatta, Sekou Touré, Kenneth Kaunda, ... this Summer of the Frontline States' aiding rebels' fight to defeat the White-supremacist Government

headed by Ian Smith in the then Rhodesia, this Summer also of Bob Marley and the Wailers' "Punky Reggae Party" and the ,Sex Pistols' still timely "God Save The Queen" (#1

in the U.K., June of 2022).

Fences of black spiked steel protected Embassies' orchids and roses and lawns green as fairways.

The beach itself often had only a few on it if the day was overcast.

So it was this Sunday. A couple farther south along the sand lounged on a blanket beneath a recumbent beach-umbrella. Closer to my left two young Blacks flipped a Frisbee in leaping exchanges.

"You are going swmming?" the taller of them, facing me and farthest away, said.

"Yep," I said. "It's always a good day for swimming."

"We swim!" The taller Black stepped toward, forefinger lipping the Frisbee, his companion now turned around and examining.

"Yeah? Well, should we go swimming?"

"You want to go swimming with us?" He approached stood with a tenative but expectant smile. He had high, orbicular cheekbones and a rangy torso of broad shoulders. I saw now that he was little over six feet tall and likely in his early 20s. His friend was comparably young but slighter in build.

"Sure. That would be great!" I said.

Over several weeks in Tanzania I hadn't had anyone swim with me in Oyster Bay or by the Harbor.

"We are from Bukoba," the taller one said.

"Bukoba! Bukoba is a long way away," I said. I'd considered Bukoba when planning the

bus-trip that ended in Ngorongoro. Bukoba was past my first intended destination, Mwanza, and almost to Uganda in the north.

"It is beside Lake Victoria. We learned to swim in Lake Victoria. We have never swum

in the Ocean."

"Well," I said, "you'll like it, I think. The water is--heavier. Stronger. But I think you'll like it."

"We are very glad," he said and looked to his friend. "We go swimming with this

man," he encouraged his friend with certainty. "We are here in Dar to study but we have never been to this beach."

They already were wearing shorts. I took off my slacks and orange Princeton Tigers (of Princeton, Illinois, nearby Lasalle/Peru, Illinois, my home for two months of Winter into Spring 1971) T-shirt and running-shoes of long-forgotten cheapness. We hid their Frisbee under my clothes.

We waded into water that was warm but refreshing to my sweat. "I just like to dive in." Ah, how good the first dunk. immersion--then the thrust out underneath breaking waves--and then the surfacing with head flung back, felt

The two young Blacks from Bukoba were swimmers who perhaps had not been taught the Australian crawl. Their arms' strokes were wide. Their palms came down flat into water. Waves caught them flush in the face and in the middle of their breathing. How they had to struggle made me wince and worry. About 200 yards out from shore, the Ocean's bottom now far beneath our feet, the younger one stopped and treaded-water. He coughed out salt-water that he'd swallowed. Waves bobbed our heads. His eyes were wider. He appeared to be near anxiety.

The Ocean rocked us side to side as well as back toward shore. "Are you alright?" I asked.

"We are good!" his friend said. "Your swimming is very good. We go with you!"

"U'mm," I said doubtfully. "I don't know. But we can go a little farther."

As a rule of both nature and nurture I'm crazily competitive. Years of sports had taught me that the aim of any activity is to go hard and to win. I stroked farther out with as much speed and technique as I could muster, something less than 100 yards, and stopped, feeling more churned and alone, to look back.

I could glimpse only the taller Black's head in Ocean water rolling both sideways and

toward shore. My heart caught.

"Your friend?" I shouted. I'd seen too many people hurt to not fear the worst. "Where's your friend?

The taller one's right arm rose and slapped a wave. He sunk out of sight and then came into sight again, "He goes back. He does not swim that much."

"We should go back," I shouted,

The taller one's wide strokes advanced toward me, he also rolled by Ocean side to side.

"We go to the ship!" he shouted back to me.

"The ship?"

In truth I knew he meant one or more of the dark-hulled freighters that were anchored about one mile offshore, awaiting their unlading in Dar's harbor. On prior Sundays I'd thought of swimming that far out and surprising whomvever might be on Deck. I'd decided that the risk wasn't worth the surprise and subsequent.

"We go to the ship! We can go to that ship, out there! You can swim and I am from Bukoba!"

Although the Ocean rocked his head and torso in a constant wobble, his eyes were alert. He looked glad and gratified and ready for triumph. Not he of us would turn back! I thought later that he'd probably never been so far from shore in Lake Victoria.

"No--I don't think so," I shouted as his wide, waves-slapping strokes brought him close. "It's too far. We've done great, but we can go back! We should go back!" I wished that I knew his name

He smiled more. He was showing me and himself what he could do. And he dipped his head into the waves and managed strokes that scarcely crested water.

"Goddamn it!" I muttered. I swam with a burst of angry energy, passing him, and

turned again after another 50 or so yards (meters) farther out.

"Now we go back!" I shouted. The taller Black was 10 or more yards away. Any one on shore--his friend the lounging couple--was too small and indistinct to be made out,

"I'm going back!" I shouted. "I'm too tired. Tired! I'm going back, and you came back with me. What's your name?

"What?"

"What is your name? I'm going back. I need you to come back with me!"

"Arnold!" he answered. "I am Arnold. You don't go back. We are going to the ship!"

His eyes were so wide and his mouth so often catching salt-water that at last appeared

uncertain of his predicament. We were like buoys tilting up and down in a boundless

washing-machine, arms and legs treading water.

"I'm going back. No question! I'll race you! I'll race you to the beach!"

With a contraction of my stomach I rolled my shoulder forward with a wave. At once the swimming was easier. "Come on!"

"You go? You are quitting?"

"Come on! We race!"

Once I saw that the taller Black--Arnold--followed, the stroking into shore felt like Don Schollander's. A fish's--a barracuda'a! A swallow's flight! Such a relief! Arnold was there, more balanced with this rock the waves, every time I looked. Adrenalin was so high that mysteps onto the Ocean's bottom--sand and oyster-rugged rocks--sprang up through the breakers as if in a grass-drill. I was very glad we were both alright.

Arnold waded from the breakers with his head nodding. "You saw?" he said to his friend on the beach. "You saw how far we go?"

"You were out there! You swam very far!" His friend was relaxed in the shared triumph and safety. "You went veryfar. I couldn't see you!"

"We could go to the ships! Next time, we will go to the ships!!" Arnold nodded me and then to his friend. "We are from Bukoba. The boys from Bukoba! Bu-ko-ba!" He said

their hometown's name like a football cheer.

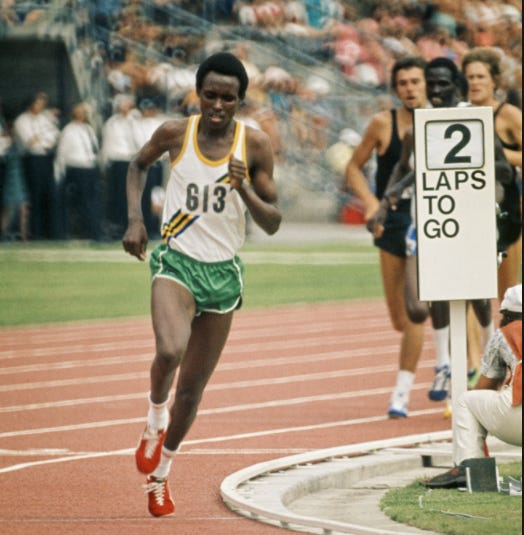

We played Frisbee. We flicked and snagged the rimmed green plastic disc on the overcast beach. I learned that Arnold was studying Drafting and his friend Khari was studying Accounting. They were committed to going back to Bukoba when they finished school. We agreed, too, that Filbert Bayi, then still the holder of the World Record for the Men's 1500 Meters that he'd set in New Zealand at the Commonwealth Games three years earlier, was a great example of boldness and determination.

"Bayi is from Karatu. Karatu is a village that is close to Arusha," Arnold told me. "Bayi is great for Tanzania! He is an example for us!"

"Well, you two did great today. Skookum Tumtum, as Northwest Coast Indians say. Stout hearts!"

20-year-old Filbert Bayi set his World Record for the Men's 1500 Meters by front-running

from 400 meters on at the 1974 Commonwealth Games Championships in Christchurch, New Zealand. Bayi's 3:32.16 lasted as a W.R. till broken by Sebastian Coe in 1979.

Don Paul set the World Road Best for running 50 kilometers in New York City's Central Park, 1982, 2:50:55. Thompson Magawana of South Africa ran his spectacular Best of 2:43:38 during the 56-K Two Oceans ultramarathon in South Africa, 1988. Magawana's

road W.R. endured for 33 years.