Steady to Grace: One Season in the Life of Bill Rodgers

Autumn of 1980. New York City and Boston

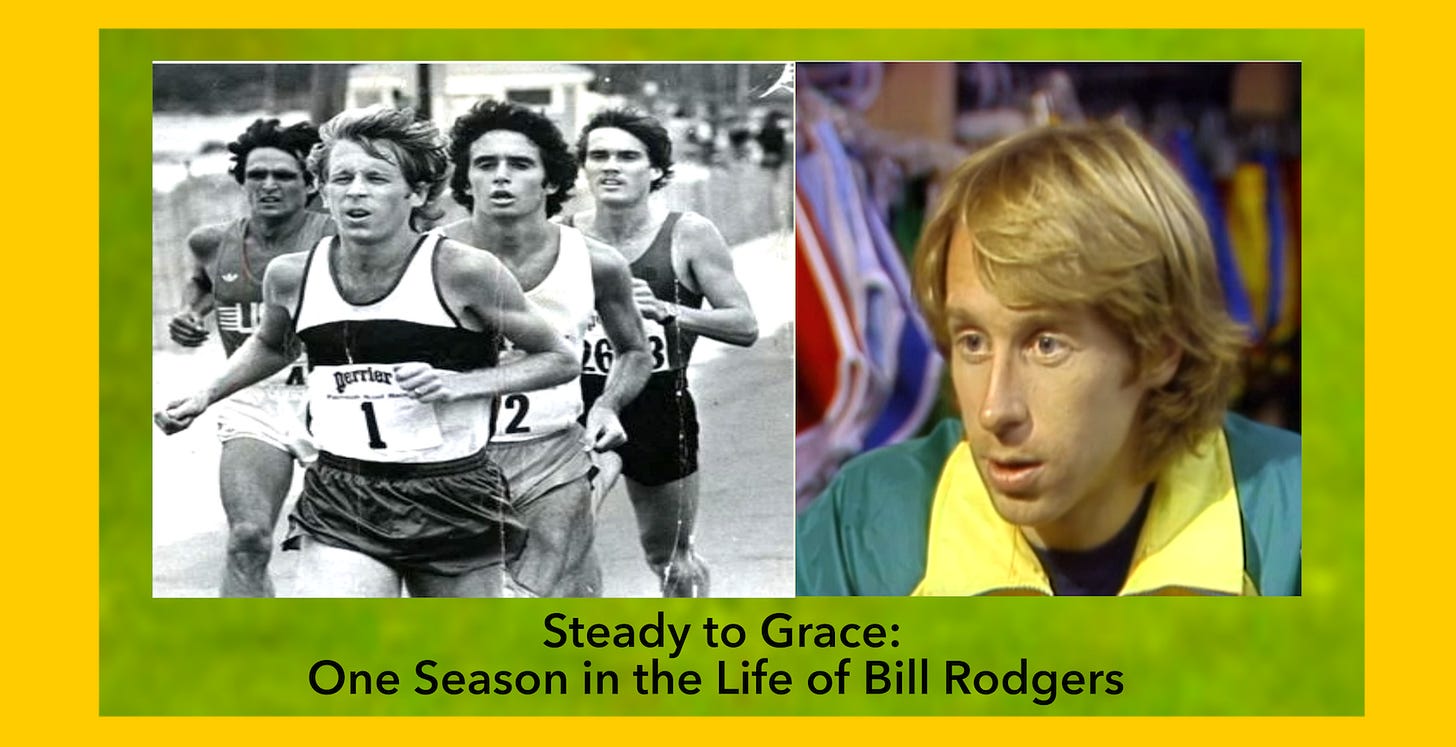

Mike Roche, Bill Rodgers, Alberto Salazar, Craig Virgin—Falmouth 7.1-mile road-run 1978. Bill interviewed before Boston Marathon 1979.

March 18, 2023. I hope that you enjoy this remembrance of distance-running circa 1980. I wrote this profile of Bill for The New Yorker ‘way back then. I love so much about distance-running and the people it’s let me meet.

Everything that I post on Substrack is free. Please think about a Paid Subscription that will enable more to happen here.

THE IMAGE OF INSOUCIANCE MASKS AN ADAMANT WILL

We know the bobbing blond hair and sylphlike stride. We know how easy Bill Rodgers looks when he’s running within himself.

His face under stress we’ve also seen in magazines--his mouth a pinched 0, his close-set blue eyes squinting.

We’ve seen, too, his triumphs and his sag into the arms of help at the Finish of a major Marathon.

Since 1976 Bill Rodgers has won his home-town Boston Marathon three times and won the even larger New York City event four straight years. He hold both Marathon’s Course-Recrods. He’s set U.S. Records for 15, 20, 25 and 30 Kilometers on the track. He’s won 16 road-races in a row, including the United States’ most competitive, the Falmouth 7.1 miler in a Course-Record of 32:21.

Pictures of the United States’ leading marathoner have gone round the world.

Another image of Rodgers is less well-known. Around the 10-mile mark in the 1978 New York City Marathon, Bill Rodgers matched with Garry Bjorklund’s fierce, sub-5:00-per-mile pace, they side by side on a warm day, their ‘duel’ much-hyped in media over the preceding week. Bill looked toward Ellen, his wife. She was fretting—urging him to slow down. Bill responded to the chiding by ... sticking out his tongue at Ellen. Albert Einstein had stuck out his tongue—given the same sign of impish insouciance—to photographers on his 72nd birthday.

In 1980 pressure is building with Rodger’s return to run for “a fifth straight title” in New York.

On a balmy Tuesday evening in late September, one month away from the Marathon, Bill is to be a presenter at the Women’s Sports Foundation’s inaugural Awards Program. The banquet is held in the venerable Plaza Hotel, 5th Avenue and Central Park South. Bill and I have drinks in the Plaza’s Oak Bar beforehand. He’s dressed in black-tie. At the banquet servers deliver modest plates of roast beef au jus, asparagus and potatoes. The meal is tiny beside an endurance-athlete’s norm. Dessert is dishes of gelatino ice-cream and assorted sweets on silver salver.

A woman poises behind Bill’s chair. She taps his shoulder. “We need you back there,” she says of preparations active backstage. “Didn’t you know?”

Hurriedly and apologetically Rodgers stands. “I wanted to eat both desserts,” he explains.

BOSTON, HIS HOME TOWN

His nature and his routine in his home city of Boston help to remove Bill Rodgers from hype.

I go there by train and talk with Bill’s brother Charlie in the original Bill Rodgers Running Center, a hub for runners, in Boston’s outlying Jamaica Plain.

Charlie Rodgers has the solidity of a retired linebacker and the mien of a New England hippie. He has shoulder-length hair and a handlebar mustache. He remembers Bill when the brothers were playing sandlot football as boys. “Billy would go in for a drink of water and not come back. He’d pick up a book and forget about our game. He just gets into whatever he’s into and blanks out everything else.”

Bill’s pleasure as he runs can be like a dancer’s enjoyment—or like an audience’s appreciation of performance. ‘You may find a beautiful place that you may have missed in your life,’ he writes in Marathoning, the book that he co-authored with Boston Globe columnist Joe Concannon, about his love for running along trails in New England during early Spring or early Fall.

Yet Rodgers has the fixity of will to have won 14 of the 17 major Marathons that he’s entered since 1975.

He’s recreated himself. In 1972 and at age 24, Bill Rodgers was smoking a pack of cigarettes a day—drinking a lot, too—while he worked at transporting corpses as a Conscientious Objector to the Vietnam War. Serendipity struck. Someone stole his motorcycle. Bill had to get to and from work. By necessity he returned to the distance-running that he’d quit upon graduation from Connecticut’s Wesleyan College in 1970. He then re-evolved. His book with Joe Concannon credits his marriage with Ellen and his resuming his sport for being ‘the critical factors in my return to real life.’

Bill Rodgers has found expression that enables emergence and fulfillment of his self. This Autumn in New York I’m reading Kant (Critique of Pure Reason), Kierkegaard (an Anthology edited by Robert Bretall), and one who will become a lifelong favorite, Spinoza (an excellent bargain from Dover Books that includes ‘On the Improvement of the Understanding / The Ethics / Correspondence’) while staying in a room on West 71st Street about five blocks from Central Park.

As always, I copy excerpts from the books I’m reading aday-to-day notebook.

Soren Kierkegaard: ‘ ... yet if you have, or rather if you will to have the requisite energy, you can win what is the chief thing in life—win yourself, acquire you own self.’

Benedict Spinoza saw that harmony with nature—the harmony that translates to living well with God—is achieved through accord with one’s own most vital drives. He wrote: ‘Desire is the essence of a man ... that is, the endeavour whereby a man endeavours to persist in his own being.... ‘

Spinoza also wrote in his Propositions: ‘To act absolutely in obedience to virtue is nothing else but to act according to the laws of one’s own nature.’

Presenting one award at the Women’s Sports Foundation’s banquet, Bill Rodgers has to read rather complicated language of the W S F’s that commends the Association for Intercollegiate Athletics for Women and its advances on behalf of female athletes since Title IX became law in 1972. Bill steps to the podium with a bounce. He delivers the citation with hearty conviction and no hitches. He returns to our table and exhales unobtrusively. His mouth is an 0, his eyes high and wide.

“I think my heart-rate must be four times what it is in a Marathon,” he says.

FRED LEBOW, PATERFAMILIAS

OF THE NEW YORK ROAD RUNNER’S CLUB

The President of the New York City Road Runner’s Club, Fred Lebow, holds up a clip of pink message-slips. The palm-size sheaf is almost as thick as a bagel.

“These are the calls I have to answer today,” Fred tells me on Wednesday afternoon, October 1, 25 days before the 1980 New York City Marathon.

The President sits behind his desk in one rear corner of the Road Runner’s headquarters on the second floor of Manhattan’s West Side YMCA. Fred’s space is largest of the NYRRC staff’s, but all are crowded together. This 1930 YMCA’s design by Dwight Christopher Baum is of terracotta and leaded glass windows. Its tiles are lustrous from linseed. The building is statement for the Y’s overall success as an institution then. Now the New York Road Runner’s Club’s part of the building’s whole is a utilitarian work-space that would be at home in New Jersey or Utah facilities’ unpretentious pursuit of goals.

The office’s energy, however, is all New York City’s. Urgency permeates the mundane as telephones ring and conversations press for answers.

Fred Lebow wears the NYRRC bicyclist’s cap of red, white and blue. His face too has grown famous through his greeting of winners of the Marathon over the past five or so years. He seeks to celebrate them and to be himself seen. On Marathon mornings Fred is forever moving from task to task in the Finish Area next to Tavern on the Green. This afternoon his half-lidded blue eyes have the guarded poise of a fox observing the entry of an intruder into its territory in, say, Carpathia.

Fred Lebow’s history, as told in 1980, is a colorful immigrant’s tale. He escaped Romania in the year following World War II,. he was just 14. He scuffled across Europe. He found ship’s passage to America. He made a success in Manhattan’s Garment District. He played tennis as his sport.

Then Fred Lebow got hooked on running. “I hated to lose at tennis, but in running I could not lose,” he’s said.

With Fred Lebow as its sole sponsor, the New York City Marathon began in 1971 with 126 entrants. Its course was loops within Central Park. Its growth exploded when it—promoted in a crucial partnership with Manhattan Borough President Percy Sutton of Harlem—became a cross- City event in 1976.

That Olympic year the NYC Marathon expanded to streets of Brooklyn, Queens and the Bronx in its route. Bill Rodgers won in a standing Course Record of 2:10.10, more than three minutes ahead of Olympic Marathon gold-medalist and silver-medalist Frank Shorter.

In 1980 the NYC Marathon’s field is full to its limit of 16,000-- with 20,000 other applicants rejected. By many measures New York’s is the world’s biggest Marathon.

“It’s Fred’s baby,” I’ve heard from several of the New York Road Runner Club’s staff.

Key staffers come from across the United States. Allen Steinfield, chief of technical operations for the Course of the Marathon and for the more than 100 other road-races that the Club organizes per year, attended the University of Alaska. Alice Schneider, designer of entry-forms and compiler of Results, is from Michigan. Patricia Owens from California “coordinates” Invited Athletes when not at her salaried job for Off-Track Betting.

Among other key volunteers, Bill Noel and Emma Jarvis are from the South. George

Vallasi, Barry Monaghan and Lenny Nemerovsky are yeoman at logistics. Merle Myerson and Brian Caulfield are Editors of the Club’s magazine.

They’re all busy this afternoon, intent at desks that some have to share, and their dress, hair, and manners remind me of groups of artisans from bohemia and the working-class such as Dickens and Orwell delightfully describe. They’ve found a home in which to be useful and gratified in the crosstown traffic of this City.

“About how many pieces of mail do you get a day?” I ask Fred.

He ponders a moment, studies his questioner, and lifts as if to weight it a hand’s breadth of envelopes—-the take from a single one of over a half-dozen stacks on his desk.

“Like this,” Fred says.

I know from prior days and nights that Fred works 12 to 16 hours most days at the Club. Most nights, he’s here at the Y past 10:00. He may stay later, if he’s not meeting his “girlfriend”, the journalist Connie Bruck of The American Lawyer. He reserves 5:00 to 7:00 p.m, Middle America’s dinner-hours, for returning phone-messages.

Editors Merle Myerson and Brian Caulfield approach the President. They ask if he, their Publisher, has seen the issue that’s just back from the printers.

“I like it. It looks very good. Very good,” he says.

Myerson’s and Caulfield’s postures lift with pleasure and they depart.

“What would you say is your main gratification from the Marathon, Fred?” I ask.

He dips his head again under the cyclist’s cap and once more deliberates with a reckoning stare. “Well, I started about ten, eleven years ago in this--running. So, it’s like graduating from college--or starting a family, having a child.”

“Do you ever think about starting a family, having a child?” “The Marathon consumes me. Children don’t consume me.” Fred Lebow answers.

Later this afternoon, Fred tells me about a brother in Brooklyn whom he hasn’t seen in one-and-a half years. With the deep-seated pragmatism of a once teen-aged refugee—a philosophical pragmatism like that of music-promoter Bill Graham in San Francisco, I think—Fred muses then: “In a way, I’ve given up my family.”

Someone else approaches. He’s a man stooped and at least middled-aged, hair sparse enough to be individual across the crown of his head. He carries a tall white box, typical of those for memorial cakes, to the desk beside Fred Lebow’s.

“Benny, what you got there?” Fred asks.

Benny Malkasian, responsible for Sales in the NYRRC office, answers: “It’s for Audrey. For her birthday. The party,”

Audrey, I later learn, is the daughter of another staff-person and herself a volunteer.

MACY’S ON HERALD SQUARE AND AN EXPO IN THE ALBERT HALL

The Macy’s at Broadway and 34th is a flagship among flagships. Its meanings exceed that of a department-store. It’s of epic epochs fit for movies’ settings.

Its outsized five stories front 34th toward distant Greenwich Village and Wall Street. Broadway runs diagonal North/South to the East. 7th Avenue (‘Fashion Avenue’) runs diagonal North/ South toward the West. And 35th Street runs directly North from MidTown toward Times Square and Central Park.

The Palladian facades of Macy’s main building in 1901 were begun in that optimistic, imperial year for the United States of 1901. Circa 1924, 1928 and 1930, architect Robert D. Kohn introduced integral Art Deco to the main building and its additions.

Overall, October of 1980, Friday the 24th, and two days before this year’s five-Borough Marathon, the ‘Largest Store in the World’ is itself like a ... cake ... a giant, cubic cake of airy and ornate interior compartments that blend together as a Castle’s chambers blend, equal still to Frank Capra’s visions of a worker’s world both egalitarian and opulent.

Frank Shorter and Bill Rodgers, the most famous rivals in American distance-running, sit behind microphones in the Sporting Goods Department. Frank Shorter is now 32, four years removed from his Silver in the Marathon at Montreal’s Olympics and eight years from his dominant win by two minutes in the violence-wracked Olympics of Munich.

A graduate of Yale with a Bachelor of Arts (1969) and of the University of Florida’s LevinSchool of Law (1974—midway between his Olympic Trials’ victories in both the Marathon and 10,000 Meters), Shorter retains the lustered-to-the-bone cheeks of a distance-runner training at high intensity and volume. He’s certainly the greatest distance-runner in U.S. history. Apart from his Olympic excellence, he won the effectual world-championship of Marathoning, Japan’s Fukuoka, four years in a row, 1971-1974, and ranked in the top five at 10,000 Meters in four years between 1970 and 1975.

This Friday before the 1980 New York City Marathon, Frank tells the standing-room audience at Macy’s that he ran 16 quarter-mile intervals on Harvard’s indoor track on Tuesday

Spectators are craning behind rows of chairs to see the pair of seated champions. One asks how much input Bill and Frank have into the clothing that their Companies sell.

“For me, I’d say that probably anyone else in our Companies knows more about the clothing we sell than we do,” Bill Rodgers says.

Frank Shorter looks askance at his fellow New Englander. He registers shock and disapproval at so candid an admission. His eyes start like a hawk’s or an owl’s. His reserve of aloof pride is troubled when the hierarchical order it keeps is disturbed. He responds with a defensive irony that may shield him from harm.

Another in the Macy’s audience asks: “What should I wear if it’s cold on the day of the Marathon?”

“Well,” Bill Rodgers says, “wear a hat, a stocking-cap, to keep your head warm, you know, and some light cotton gloves--like the kind I sell.”

Bill then grins. The fun in him--his insouciance—comes out like a larking boy’s. Heaped on a counter behind his and Frank’s fans, however, are stocking- caps that bear the BR logo of his Company. These head-warmers are $8.50 each at Macy’s today.

Frank and Bill after their intentional tie in the Virginia 10-Miler, September 1975/

Again a song comes to my mind.

It first arose as I wrote about about Punk Rock versus major Labels’ Rock while bent of typewriter in rooms of London and Dar es Salaam in 1977 and of 5th Ward Houston in 1978.

This song’s melody and meter are like that of the theme to 1950s TV’s --Mickey Mouse Club--.

The song goes: “C-O-R----P-O-R---- Oh—oh——Oh-oh——Oh!”

Thus, C. O. R. P. O. R. O.

C. O. R. P. O. R. O. stands for Combined Optimal Retailing Of Product Overall.

In Rock this co-optation of free expression into product, this Combined Optimal Retailing ..., was seen in the form of torn T-shirts worn by the Ramones, the Sex Pistols, the Clash, ... and then sold at ... Harrod’s and Macy’s ... like Beatles’ lunch-pails.

I’ve been hearing C. O. R. P. O. R. O. song while walking through the New York City Marathon Running Expostition.

Booths of the Expo extend throughout underground Albert Hall of the Sheraton Centre in midtown Manhattan.

Browsing runners crowd the aisles. They peruse a bazaar--a bazaar for health!

Here in the Expo beneath mid-Manhattan’s constant traffic of Taxis and Buses, cars and trucks, we can sample Yogurt, Bars and Chips--for our, for runners’, Natural Health! We can page through magazines that mirror back to us images of desired fitness. We can check out cosmetics applied to our faces. Above all else we can view, handle, and try on ... shoes!

Shoes of many colors and innovations! Shoes of many soles! The trefoil sole! The Z-studded outersole! The Maxitrac or Waffle outersol! The super sine moreflex outersole!. All real, these soles.

We can test the Wear Plug System. Or the B-17. We can feel our feet treated to Reflexite—or Ultra Flex—or Natural Flex ... support.

Above the ankles? There is for us runners the accoutrement and prospect of a ‘Winged headband.’ This enhancement toward flight may be worn above ‘Bun Huggers.’

Or it may Herald O’er an Outfit of shorts and singlet in ‘sensuous pink’.... Promising more warmth and style for the Marathon on Sunday. And the BR stocking-cap will be an excellent complement for anything we wear.

A Huge New Market has opening up with the Running Boom. Business is burgeoning. Its numbers drew President Jimmy Carter to campaign at this Sheraton Centre.

Fred Lebow gave the candidate a grudging handshake, angry at the snarls to traffic that the Commander-in-Chief’s visit caused.

The glossy, costly, new trappings of running seem far from finding Bill Rodgers’ ‘beautiful place that you may have missed in your life.’ They seems far from the 170 miles a week on sleet-slick streets that both Rodgers and Shorter ran, circa 1975, in pursuit of gratificaiton that had almost no money attached to it. They seem far from what Fred said, “Hey, Benny, what you got there?”, and the cake that Benny Malkasian brought for the daughter and volunteer.

PRESS CONFERENCES

Pre-Marathon speculation by journalists is intense. We who gather to observe leading entrants like to predict outcomes.

Thursday through Saturday mornings the New York Road Runners Club administers a series of Press Conferences at the Tavern on the Green, a quick jog from the Marathon’s Finish Line in

Central Park. Invited athletes are introduced by Fred Lebow or Patricia Owens or publicist Joey Goldstein. We journalists jot down their responses.

Some of us favor Gerard Nijboer of Holland. Nijboer, 6 feet tall, strapping for a world-class marathoner, was silver-medalist behind Waldemar Cierpinski in the past August’s Olympic event. In April at Amsterdam Gerard Nijvor recorded the second-fastest time ever for a marathon, 2:09:01.

On Thursday morning in the Tavern on the Green, Nijboer is asked the flat, New-York-City- accented question: “Can you beat Bill Rodgers on this course?”

Gerard’s blue eyes remain steady as he answers: “It is a heavy track in New York, but I think I have as much chance to win.”

Saturday’s Press Conference brings Bill and Fred together. Lebow stands before photographers’ bathing glare of lights in the Elm Room, his cyclist’s cap straight above his beard. He gestures with one hand. “Now I really do not haf to introduce him, because he is--Billy Rodgers.”

Rodgers bounce-steps up to the mics. Replying with manifest earnestness to questions, he purses his lips, widens his eyes, wrinkles his brows.

Other runners wait to be interviewed. Alberto Salazar, age 22, trying his first marathon the next day, watches Rodgers. Alberto Salazar’s i gaze impatiently broods. Salazar wears a brown leather jacket with breast pockets. He has long eyelashes, a clear complexion, and an implacable air: the acolyte as gunslinger with a potential for guerrilla martyrdom.

Alberto Salazar came to the United States as a baby, his father leaving Fidel Castro’s turn to socialism in Cuba. He set High-School records in Massachusetts and went on to NCAA Championships at the University of Oregon. He and Bill Rodgers both competed for the Greater Boston Track Club. He’s run 27:49 on the track for 10,000 meters this past August. He’s said about his entry into the New York City Marathon, looking from Eugene, Oregon in June: “I want to beat Billy Rodgers at his own game.”

One reporter in the lights-bathed Elm Room probes Salazar’s unprecedented prediction of a 2:10 debut. “Do you think that’s realistic, when you haven’t run more than 20 miles in training?”

Alberto Salazar juts his lower lip. “I’m as well-conditioned as anybody in this field. If somebody else runs 2:10,” he says, “I’ll run 2:10.”

RACE-DAY

The morning of the Marathon is ideal for distance-running. Cool--mid-40.s--and overcast, it further helps the more than 20,000 starters with a northeasterly wind.

The international telecast, fed to Europe and Japan, is frustrating to watch. It’s in fact incomprehensible in its shortcomings and lapses.

Around 8 miles the lone camera on the lead pack in Brooklyn--then numbering about twenty, with Rodgers, Salazar, Filbert Bayi of Tanzania, and Dave Chettle of Australia among them--somehow fails. There is no back-up. “It looks like we’ve lost transmission from our camera there,” says Bud Collins, his expertise tennis, to his fellow anchor at the Finish in Central Park, Frank Shorter.

For about 40 minutes we who watch TV have only overhead shots from a helicopter on the men’s race. We see the lead group advance along streets like a a slender bead through channels. We lose sight of them completely when they pass over Bridges.

Rodgers is reported to have made a break, to have opened a gap of 40 meters. The breakaway runner turns out to be Steve Floto, not the world’s most publicized marathoner. A camera waits on First Avenue, the Manhattan end of the Queensboro Bridge, by the 16-mile mark. “It’s going to be very exciting to see Bill Rodgers come out of the whip of this ramp off the Bridge, with thousands of spectators cheering him, and two or three other runners right behind him,” Shorter says. “We know from the splits that they’ve run the first half of this Marathon on Course-Record pace.” On-course commentator Larry Rawson then reports that Rodgers has fallen between miles 14 and 15, tripped among a group of six up the slope of the Queensboro Bridge.

Five runners come off theBridge together and stay abreast up First Avenue. They are: Alberto Salazar, the comparably young Jeff Wells and Dick Beardsley of the U. S., John Graham of Scotland, and Rodolfo Gomez of Mexico. We who watch TV monitors in the Tavern on the Green now have at least a camera on the men’s race. Graham surges first. Salazar and Rodolfo Gomez, both schooled in track-racing, cover the move. Dick Beardsley falls back to Jeff Wells, 20 meters behind. The three leaders progress like soldiers of different armies in pursuit of game, their strides low and their torsos unchanging. The two Latino runners open a gap on Graham by Mile 21.

The breeze becomes a headwind. I’d tested it earlier in the morning, running back from 125th Street in Harlemalong 5th Avenue. The headwind had blown my posture backward and skitteried bottles across pavement. Stronger now, it appears to affect Salazar least. His legs extraordinarily long and lifting little in the green and gold of his University of Oregon shorts and singlet, his arms swinging like an engine’s rockers, he keeps his head and shoulders optimally level. The 22-year- old’s gaze is even more fixed than at the Press Conference.

Gomez, age 29, winner of the 1979 Pan-American Games 10,000 Meters for Mexico and 6th in the 1980 Olympic Marathon, rather shorter and slighter than Salazar, concentrates with a desire that betrays flickers of desperation. He falls one stride, then another, behind, and slows to grab a paper cup of water off a table. Salazar surges definitely. The space that Gomez must make up extends to 10 and then 20 meters.

The TV coverage cuts to commercials. It cuts to commercials!

How many shouts and groans leap from viewers’ throats at our losing sight of the race! It’s as if coverage has jumped from Dr. J in mid-flight during the NBA Finals--or from Borg and McEnroe in mid-volley at Wimbledon--or from rival yachts rounding the last buoy in the America’s Cup--or from ... The break in coverage feels like an ignorant slight to the stature of marathoning.

When we next see Salazar he’s even more alone and commanding. The green and gold of his U. of Oregon shorts and singlet suit Central Park. His shoulders are like a T-bar. His stride is of rocker-arms and pistons and his physique is lean as Abebe Bikila’s and other Records-setting predecessors. His gaze no more wavers than his strides.

The Greater Boston Track Club’s “Rookie” crosses Central Park South, turns up the Park’s West Drive, accelerates into a last, little hill and past the Finish-Line says into the arms of Fred Lebow and three more NYRRC staffers. Salazar has set a Course-Record and a first-time marathoner’s best: 2:09:41. Only Bill Rodgers’ 2:09:27 at Boston for 1st in 1979 is faster by a U.S. athlete.

Rodolfo Gomez finishes in 2:10:13, a best for himself and Mexico. John Graham and Jeff Wells are close, 2:11:46 and 2:11:59.

Then an electric, welcoming ovation carries above TV-coverage in the the Tavern on the Tavern on the Green’s Press Room. “Bill!--Bill!” sounds from the crowd in bleachers that flank either side of the finishing straight. Bill is rather slumped in 5th place this cold and windy day. Across the Finish he hunches forward, gloved hands on his scraped knees.

The next great, rolling roar from the New York crowd is: “Grete!--Grete!”

Fred Lebow skips beside the champion to the Finish--his peculiar run of one arm cranking to hurry him along. Grete Waitz is by this year a heroine in New York City. Four times the Norwegian has raced this Marathon; each time she’s set a Woman’s World Best.

Today Grete Waitz’s shocking time of 2:25:41 is nearly 2 minutes faster than in 1979. Patti Catalano is second woman, clenching her hands ecstatically as her 2:29:34 makes her the first U. S. woman under 2:30.

The post-race Press Conference, Awards Ceremony, and private Party follow on this Sunday.

More of the runners’ characters comes out. Alberto Salazar stands under photographers’ lights in the Tavern on the Green’s Pavillion Room. “I don’t try to be cocky,” he says. “I try to to be

honest. If somebody asks me I’m going to tell him what I think.” His first marathon the seventh- fastest time ever run, he says: “Someday I can run under 2:08.”

Bill Rodgers, wearing a BR warm-up suit and stocking-cup, sits next to John Graham at a table to one side. His “spill” hadn’t affected his overall race, he says. “No one was going to beat Al Salazar today.”

Yet that evening Rodgers’ eyes narrow as Salazar accepts the winner’s Samuel Rudin Trophy at the Awards Ceremony in the Sheraton Centre’s Albert Hall. His jaw tightens, its line jutting--a little of “the animal” in this athlete is manifest. Patti Catalano praises “the great crowds and support you get in New Yawk.” Grete Waitz is matter-of-factly gracious in her gratitude, queenly in her demeanor, as composed on stage as she was in the race.

The party at the Old Stand on Third Avenue, hosted by adidas, plays Disco and Rock through speakers by the bar. Drinks loosen up runners particularly after their Marathon. The high of endorphins spills out into movements almost violent in their expansive vigor. How each senses rhythm is often different. Alberto Salazar stands at ease and aglow, surrounded by friends from Oregon and Boston. He laughter is shy but of relief from his triumph. Bill Rodgers first keeps his distance from the dance-floor. He’s then persuaded to try “a slowish dance.” He winds up dancing fast and with an aplomb like that he showed in reading his announcement at the Women’s Sports Foundation.

BACK ON OLD PATHS

By Friday of the following week Bill Rodgers is up to 15 miles a day, he tells me over the phone. “I’m running some of my old routes and beginning to feel a little snap come back.”

He has a Marathon in Rio de Janeiro on November 17, little more than two weeks away. For 1981, he has the Houston Marathon on January 10 and “probably” the Tokyo International in late February . These three were already Marathons in Bill Rodgers’ prospects before he returns to Boston in mid-April for defense of his 1980 win there.

“What do you most want to do as a runner now?” I ask.

“Well, I want to get under 2:10 again,” he says. “And I want more of major wins, ya know.”

“What about the World Record?”

“Well, yeah, I see what you mean. The problem is the races you would have to give up, ya know, and the income. Let’s see, if I put in three months of just training that would mean about ten races I would have to miss. It’s a gamble. Peaking is always a gamble.”

“How does Alberto’s run seem to you now?”

“Pretty amazing. It was pretty amazing. I always seem to be there when a guy breaks through.” He remembered 22-year-old Toshihiko Seko’s win at Fukuoka in 1978. “But it’s not as easy as I think Al thinks it is. After all, he’s not any different from any of us. If by nineteen eighty-three he’s run ten Marathons and they all go well for him, then I’ll change my tune.”

“So you’re not going to change your training, your approach?”

“No,” Bill Rodgers says. “Why should I?”

Bill once more reminds me of philosophers and artists.

‘Again, as virtue is nothing else but action in accordance with the laws of one’s own nature, ... it follows, first, that the foundation of virtue is the endeavour to preserve one’s own being, and that happiness consists in man’s power of preserving his own being,’ Baruch Spinoza wrote.

Vincent Van Gogh corresponded with his brother Theo from his fluorescent season of artistic harvest at Arles. Oleanders and stars were afire for Vincent then. He wrote to Theo: ‘These colours give me extraordinary exaltation. I have no thought of fatigue. I shall do another picture this very night, and I shall bring it off. I have a terrible lucidity at moments when nature is so beautiful; ... I can only let myself go.’

Bill Rodgers must feel something kindred. He takes in. He gives out. He finds around corners and in sunsets “a beautiful place” that he hadn’t yet known in his life. Everything is exploration. Everything is enriching. All arives at more of who Bill is. We may imagine him running forever. That wave from a carefree being in self-fulfilled, generous freedom. That squint of digging deep. That O of wonder and of working, building, toward exaltation. The earned and transporting revelations and triumphs. This runner.

Don Paul, September ro November 1980

Oct. 11, 1980.

JAMBAR in 2023 is providing excellence and generosity like Bill Rodgers throughout his lifetime as a world-renowned runner. JAMBAR, the new ‘Organic Artisan Energy-Bar’ from Jennifer Maxwell, comes in four kinds: Chocolate Cha Cha, Jammin’ Jazzleberry, Malt Nut Melody, and Musical Mango. Jennifer was co-creator of the Ur energy-bar, Power Bar, back in the middle-1980s day.

Jennifer and Brian at the Houlihan’s road-race, March 1987.

Each kind of JAMBAR has a musical theme that embodies its ingredients. The Cha Cha and the Jazzleberry and the Melody and the Mango are each loaded with primary sources—high-quality, organic chocolate, or berries, or maple syrup, or mangos.

“They taste great,” as Kirk Joseph, sousaphonist for the Dirty Dozen Brass Band, sings. They’re “delicious and nutritious”, as American man of music David Amram says. They ‘satsify my taste buds and work well with my nutritional values’, the ‘greatest woman athlete of the 20th-Century’ (Sports Illustrated), Jackie Joyner Kersee writes.

JAMBARs also do good. JAMBAR sponsors 18 Partners in Music and/or Active Living.

JAMBAR, in short, is a throwback to good and giving times. For years before the late 2021 arrival of JBs in the SF Bay Area, Jennifer supported efforts by Sticking Up For Children in Haiti and New Orleans. Over the past year JAMBAR has donated more than 2000 Bars for students who truly need nutrition in Port-au-Prince and Cayes Jacmel.

You can check out the glories JAMBARs here.

Thank you Sir. Exciting & excellent glimpse into a whole other world & sport.