"Oppenheimer" as Cinema: Cause for Celebration

Re-opening vistas into real people, complex conflicts, and epoch-changing events

Responding to a creation with gratitude and praise is always a nice, uplifting and expanding thing.

The creation might a short-story, or excerpt from a novel, read in the fourth-floor Jones Room of the Old Library on Stanford University’s campus to our class of Creative Writing Fellows and other students, Spring of 1972.

It might be flights of Eric Dolphy’s and companions on his album Out To Lunch.

It might be the great reach of Gravity’s Rainbow, or the fantastical wisdom of Sun Ra, or the wry resolve of Sonny Liston.

It might be Thomas Mann inspired and inspiring in ‘Goethe and Tolstoy’ and ‘On Schiller’.

“Oppenheimer”, the 2023 movie by writer and director Christopher Nolan and his team, gives us such access into gratitude and praise. “It’s so good!” says a new friend.

“That was a very fast three hours,” I said to Maryse when “Oppenheimer” finished in one theater of the Broad in New Orleans one Tuesday nightin early August. “It was great,” she nodded definitely. “Great,” I said.

Achievements of “Oppenheimer” and Christopher Nolan and his team are multifold. The movie succeeds as spectacular cinema. The Trinity BOMB explodes in an uncoiling fireball that envelops sky.

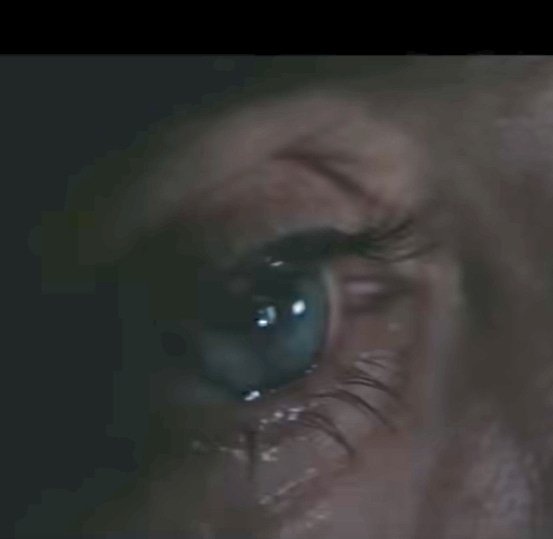

“Oppenheimer” travels through real-life settings various as Cambridge University lecture-halls and plano vistas of New Mexico with painterly fidelity. Hoyle van Hoytema is the cinematographer. It renders psychological states as vividly. Oppenheimer as a graduate student at Cambridge and at Gottingen, studying with Max Born, Nils Bohr and Werner Heisenberg, sees premonitions of destruction with a haunted eye.

Soundscapes by composer Ludwig Gorannson vary with intense acuity, too. They embody interior states as they do the ambiance and pacing of 1930s Leftist Faculty parties and 1950s hearings in Washington, DC.

“Oppenheimer” shifts between six major settings and time-spans—Universities of England and Germany in the latter 1920s and early 1930s; Cal Tech and U.C. Berkley in the 1930s and early 1940s; the Perro Caliente (“Hot Dog”) ranch of Robert and younger brother Frank in northeast New Mexico and the Sangre de Cristo Montains; the Los Alamos military-base and testing-ground for the Manhattan Project from 1942 into 1945; the secretive, small-room Atomic Energy Commission hearing in Washington, DC, that concluded with revocation of Oppenheimer’s security-clearance in Summer 1954; and the U.S. Senate hearing for the nomination of Lewis Strauss as Secretary of Commerce in June 1959. Everything flows in the intertwining shifts between settings. Everything connects. Everything advances our engagement with the movie’s characters, story and whole.

The cast is superb. Cillian Murphy embodies J. (Julius) Robert Oppenheimer as a leaf does light. Oppenheimer’s energy! That always seeking energy! The slender, sharp-boned “Oppie” can be so focused that he verges on breaking. Yet his self is never complete. He’s never quite sure. Perhaps he knows too much his colleague Heisenberg’s Uncertainty Principle. He assumes props such as his wide-brimmed hat and the nervous constants of cigarettes or pipe. His self finds a consuming goal in the Manhattan Project—building an fissionable Big Bomb “before the Nazis”.

However, the womanizer’s energy is most grounded, most straightened up and shaped up. by his wife, Kitty. Emily Blunt plays the former Katherine Puenig. Kitty is a botanist and writer. She’s as forthright as her gait and her handling of a galloping horse. She’s the common-law widow of a Communist, Joe Dallet, who died while fighting for Republicans against Franco’s and Hitler’s Fascists in Spain’s Civil War. Her biography is on the American Heritage Foundation’s website.

Kitty in the 1930s during her common-law marriage with Joe Dallet.

Florence Pugh plays Jean Tatlock, a student, writer, and eventual psychiatrist and writer who met, challenged and fascinated Oppenheimer from 1936 onward. Jean tosses the older suitor’s bouquet of flowers into a trash-can. She commands him to prove. that he can read Sanskrit. Her own mood-swings contort her postures.

When Jean’s sudden death in January 1944 (by suicide? by assassination?) shatters “Oppie” in Los Alamos, Kitty shakes his cringing shoulders.

She’s as steadfast then as she is in her precise and cutting answers to Oppenheimer’s prosecutor Roger Robb in the 1954 Atomic Energy Commission hearing (see Erica Gonzlez’s profile in Elle) and as unyielding as she is in refusing to shake Edward Teller’s hand during the late 1963 White House ceremony (one week after John F. Kennedy’s assassination) that awarded her “rehabilitated” husband the Enrico Fermi Award and $50,000.

Leading male actors in “Oppenheimer” play to the level of Cillian Murphy. Matt Damon is Brigadier General Leslie Groves. Steady gaze. Jaw blunt as one wedge of the Pentagon, a building that Groves was principal in constructing from 1940 forward. Groves (Damon) shrewdly recognizes that Oppenheimer’s ambition and charisma makes this academic a fellow commander. Robert Downey plays Lewis Strauss, Chairman of the Atomic Energy Commission betweenbn 1953 and 1958. Strauss’ maneuvers to strip Oppenheimer of a National Security Clearance in 1954 and to win as Eisenhower’s nominee for Secretary of Commerce in 1959 provide most of the movie’s drama in its final hour. Strauss as depicted by Downey and Nolan is perfect in preening pretensions (white tie and scarf) above roots of insecurity and mendacity. As a Trustee of Princeton’s Institute. for Advanced Study, the amateur physicist Strauss sought Einstein’s approval, sought Oppenheimer’s approval, and and then sought secret vengeance after his rebuffs. Dialogue involving Strauss (Downey) is particularly sharp as he’s by stages revealed.

Rami Malek plays Mississippi-born physicist David L.. Hill, colleague of Enrico Fermi and Leo Szilard in the Chicago Pile’s developments of chain-reaction. Hill (Malek) delivers the most crushing tell against Strauss at the Senate hearing of 1959.

(A sidelight. Two more physicists who fled NAZIs’ Germany, Leo Szilard and Lisa Meitner, are crucial to the real-life discovery of fission through chain-reaction and then to efforts to sensibly control nuclear power and nuclear weaponry. Ms. Meitner realized in Denmark that neutrons bombarding uranium were not being absorbed but were splitting into ‘two smaller nuclei’—thus creating reaction equivalent to more than ‘10,000 tons of dynamite.’ Leo Szilard (inventor of a refrigerator with Einstein in Berlin, 1933!) led a Petition by Chicago-based scientists that asked President Harry Truman to simply “demonstrate” the awful power of “atomic bomb” and not inflict it on civilian populations. Szilard is played by Máté Haumann in the movie. Oppenheimer in real life and in the movie declines to endorse the Petition’s circulation at Los Alamos. The Pittsburgh Jewish Chronicle relates Meitner’s and Szilard’s achievements in a nice piece here.)

“Oppenheimer” is so welcome a success! An aesthetic success! A commercial success! $648 million in global box-office after four weeks. It re-opens vistas and proves that the public appreciates more than Comic-Books and Cartoons blown up on movie-screens.

Orson Welles said that if Shakespeare were alive today Shakespeare would be making movies. Akira Kurosawa said that he aspired to make movies which deliver the depths and powers of great novels such as Dostoyevsky’s. Christopher Nolan and his team in “Oppenheimer” have lit out into such open-ended and satisfying territories.

Don Paul is the author of more than 30 books and the leader or producer of 29 albums. He’s numbers-oriented. David Amram: ‘Like Shakespeare, Jack Kerouac, Langston Hughes, Virginia Woolf, and Carson McCullers. Don Paul uses words like music.’ He and his wife, Maryse Philippe Déjean, co-direct Sticking Up For Children in Haiti and New Orleans.