Mann's 'Death in Venice'

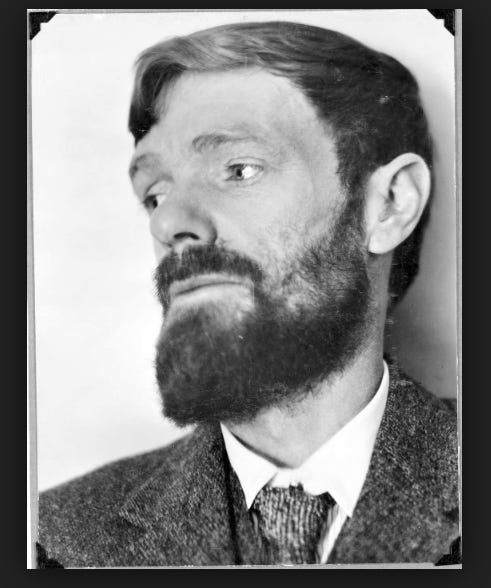

Remembering the sublime story, Mann's essay 'On Schiller', and the 'Sympathy' that he and D.H. Lawrence share.

Patti Smith’s reflections on Thomas Mann’s ‘Death in Venice’, conveyed through two videos on her Substack, inspired me to revisit the eight pages that extol this novella within my book-length essay, ‘Lawrence and Mann Overarching’, published, lo and behold, 44 years ago.

I wrote then, age 31: ‘Death in Venice is a tale of morality crucial to Mann. / To me, it’s perfect, it’s transporting, everything of it is sublime.’

I love ‘Death in Venice’ as a triumph for Thomas Mann. His story confronts conflicts crucial to Mann’s person, his social being, and his career. Thomas Mann was 36 and 37 when he fought for the transporting excellence that ‘Death in Venice’ wrung from him.

Gustave von Aschenbach is the tale’s protagonist. The letters patent were conferred on the writer’s 50th birthday, three years before we engage with the crucible that he wrestles in Venice. Like Mann, Aschenbach won fame early. Mann’s prodigiously accomplished novel Buddenbrooks, recounting four generations of a bourgeois Hanseatic family like Mann’s, published in 1901, Mann’s age then 26, was a best-seller critically acclaimed and generally celebrated. It’s a marvel of clear-sighted but loving insights.

10 years later, 1911 into 1912. Mann wrote his novella about the substantially more elder Aschenbach, a writer whose ‘new type of hero’ bears inward and inward affliction without show. Reading Aschenbach, Mann writes, one ‘might doubt the existence of any other heroism than the heroism born of weakness.’ Ashenbach navigates life like a closed fist. He’s little shorter than middle height, his hair bushy but thinning, his nose imprinted by rimless gold spectacles. His wife died soon after giving birth to a daughter who has married, Aschenbach’s only child.

Walking nearby Munich’s North Cemtetery after a morning of ‘hard, nerve-taxing work’, Ascenbach is startled by a glaring, straw-hatted pilgrim-with -rucksack into sudden vision of a tiger gleaming in the tropics. His heart throbs with terror and with longing.

He travels to Venice. In his Hotel on the Lido he’s startled again: the sight of a boy among family. ‘Aschenbach noticed with astonishment the lad’s perfect beauty. His face recalled the noblest moment of Greek sculpture, pale, with a sweet reserve, with clustering honey-colored ringlets, the brow and nose descending in one line, […]’ Aschenbach thinks that he’s never seen in nature or art ‘anything so utterly happy and consummate.’

He tries to flee his infatuation, to leave Venice, but finds in the Rail-Station that his trunk has been shipped in the wrong direction.

‘A reckless joy, a deep incredible mirthfulness shook him almost with a spasm.’

He’s destined to fulfill portents. I write on page 83 of Lawrence and Mann Overarching: ‘Days run on in a sheen of heat. Aschenbach rises not to work but to watch Tadzio.’

The artist’s travails increase. Rumor of Plague—Cholera—become that real disease, spreading within Venice’s heat. Yet Aschenbach does not depart, nor does he inform Tadzio’s mother. ‘It would restore him,’ Mann writes, ‘would give himself back once more; but he who is beside himself revolts at the idea of self-possession.’

That night a dream’—if dream be the right word for a mental and physical experience’ whose ‘theatre seemed to be his own soul, and the events burst in from outside, […]’ pitches Aschenbach further into surrender. He sees and hears wild invitations. Men and women, boys and girls, girt with hairy pelts, accompanied by ‘that cry, composed of soft consonants with a long-drawn u-sound at the end’, race downward in his sleeping concsciosuness and gather swiftly into an orgy. Laughing and howling, foam from their lips, they beckon each other, draw blood with their staves, lick it, and entwine. Then the dreamer is among them. The ‘stranger god’ that he’s dreaded is now his. He too is ‘flinging himself upon the animals, […]—while in the trampled moss there begins the rite in honor of the god, an orgy of promiscuous embraces—and in his very soul he tasted the bestial degradation of his fall.’

Next day, the artist discovers that more guests have left the Hotel and the bathing-cabins. Tadzio and family, however, remain.

Aschenbach pursues and primps. ‘Like any lover, he desired to please.’ His cheeks are rouged carmine, his lips turned the color of ripe strawberries, and his barber dyes his hair black. He follows in ‘his red neck-tie and broad straw hat with its gay striped band.’

He sinks further on steps of the city. He hears arguments from the conflcits within him. ‘Beauty alone is divine and visible, the senses’ way, the artists’ way to the spirit, but is such a path manly? Or is the artist’s way, that heroic sword-dance balanced by discipline against license, not sure to stray?’

He hears a voice like Socrates’ wooing Phaedrus. ‘Knowledge is all knowing, understanding, forgiving; […] It has compassion with the abyss—it is the abyss.’ At the same time, ‘preoccupation with form leads to intoxication and desire.’ They, too, ‘lead us to the bottomless pit.’ Poets. Aschenbach hears, ‘are prone not to excellence but to excess.’

Gustave von Aschenbach is letting go his closed-fist grip of Reason. He’s lost within the fixed whirlpool of his Longing and Desire. His choleric sickness progresses.

A few days later Aschenbach finds the Polish family’s luggage strapped and ready for departure in the Hotel’s lobby. He visits the beach for a last view of Tadzio.

The young adolsecent leaves his playmates to stand on a sandbar. He pauses there. And ‘with a sudden recollection, or by an impulse’, he turns from the waist up, hand poised on one hip, and looks over his shoulder. Aschenbach’s head lifts in answer from the back of his chair, but then dips chin-first to his chest. Still he imagines. Aschenbach’s eyelids are closed but he sees through them ‘the pale and lovely Summoner’ smile. The image, the idol of an ideal, beckons with his hand lifted from cocked hip as if ‘to an immensity of richest expectation.’ And Aschenbach, the dying artist, ‘rose to follow.’

As said above, ‘Death in Venice’ is to me in its writing inspired and involved toward perfection. Even when exalted the prose never falters. ‘Now daily the naked god with cheeks aflame drove his four fire-breathing steeds through heaven’s spaces […]’. The writing is vivid when plain. ‘A camera on a tripod stood at the edge of the water, apparently abandoned; its black cloth snapped in the freshening wind.’ And so telling is the writing, I exclaimed in 1981. ‘Thought that can merge wholly into feeling, feeling that can merge wholly into thought—these are the artist’s highest joy’, Mann gave us.

Thomas Mann worked on ‘Death in Venice’ from one Summer into the next, 1911 into 1912. He finished it while his wife Katja ‘was taking the cure at Davos, he alone with their four children at Landhaus Thomas Mann in Bad Tölz, the Isartel. The biographically true characters and incidents shot together like crystals, he recalled. “Perhaps it had to do with this: that as I worked on the story—as always, it was a long-drawn-out job, I had at moments the clearest feeling of transcendence, a sovereign sense of being borne up, such as I had never before experienced.’

Let me also recommend especially from Thomas Mann all of Buddenbrooks and Doctor Faustus, novels about his Germany, separated by 47 years and two World Wars, and his essays ‘Goethe and Tolstoy’ and—in his 80th year!—‘On Schiller.’

I wish to close this short appreciation by quoting both Mann and Lawrence as they’re cited near the end of that 195-page essay that heads the front-cover above. I lost drafts of the partly hand-written manuscript for Lawrence and Mann […] twice—first in a flophouse on Main Street in Los Angeles, the day after Christmas 1975, and then, 14 months and a painful number of Footnotes again assembled later, in a parking-lot of Grand Isle, Louisiana when I rushed to board a boat for my rookie “hitch” offshore in the oil-field. The essay was for me

In 1955 the again-exiled Thomas Mann was 79 and living in Switzerland. He was invited to address audiences in Stuttgart and Weimar regarding the 150th anniversary of playwright, poet and rebel Friedrich Schiller’s death. He dove in and went deep and wide. Katja recalls her aged husband’s fervor on page 186 of my Lawrence and Mann: ‘He worked so hard on it that it kept getting longer and longer and it finally grew to one hundred and twenty pages instead of the twenty pages which had been planned.’

Mann’s remembrance takes flight with admiration throughout Schiller’s oftens storms-tossed career. ‘It is not easy to stop, once I have begun to speak of Schiller’s special greatness—a generous, lofty flaming, inspiring grandeur such as we do not find even in Goethe’s wiser, more natural and elementary majesty.’

Mann then rails from his mid-1950s perspectives. ‘The past half-century has witnessed a regression of humanity, a chilling atrophy of culture, a frightening decrease in civility, decency, sense of justice, loyalty, and faith, and of the most elementary trustworthiness. Two world wars, breeding brutality and rapacity, have catastrophically lowered the intellectual and moral level (the two are inseparable) and left behind a state of disorder which is a poor safeguard against the plunge into a third world war […] Rage and fear, unreasoning hatred, panicky terror, and a wild lust for persecution ride mankind. The human race exults in the conquest of space for the establishment of strategic bases in it, and counterfeits the energy of the sun for the criminal purpose of manufacturing weapons of annihilation.’

That from Thomas Mann near eighty!—almost a quarter-century ago,’ I wrote in 1981—and our present, of course, has 44 more years of suffering Big Lies and infernally idiotic degradations added.

In 1955 the still idealistic Mann returned to Friedrich Schiller’s ardent hopefulness in closing to his audence at their celebration. ‘May it stand under the sign of universal sympathy, true to the spirit of his [Schiller’s] noble-minded greatness, which called for an eternal covenant of man with the earth that gave him birth.’

D.H. Lawrence, the writer who’s companion with Mann in my essay, recurred to ‘sympathy’, too.

Lawrence praised in his rebellious, raffish AND profound book of 1923, Studies in Classic American Literature. Walt Whitman’s approach to his fellow human beings. How to meet them? ‘With sympathy, says Whitman [….] Feel with them as they feel with themselves.’ Lawrence affirmed this attitude. ‘It is a great new doctrine.’

You may remember from Mann’s ‘On Schiller’, above, the 20th-century German writer urging ‘the widest possible sympathy’ and for his audience to celebrate ‘under the sign of universal sympathy.’

Sympathy may be even with stones. Page 193 of my Lawrence and Mann brings up Professor Kuckuck from Mann’s entertaining novel Confession of Felix Krull, Confidence Man. The Professor advises: ‘ “And don’t forget to dream of stone, of a mossy stone in a mountain brook that has lain for thousands of years coolewd, bathed and scoured by foam and flood. Look upon its existence with sympathy.’ Lawrence was expansive. ‘It is all the same with the worlds, the stars, the suns. All is alive, in its own degree.’

Sympathy may especially be our guide away from the Hazing Screens, promoting ‘Rage and fear, unreasoning hatred, panicky terror, and a wild lust for persecution’, in our 2025. So we may find—as I’ve found this past day in revisiting the heroism evinced by Mann through his ‘Death in Venice’—bracing steadfastness and still glowing sentiments in the lives and work of those two who so educate us about the 20th century and who still soar over Footnotes, Lawrence and Mann. Thanks, Patti!

I believe that the book Lawrence and Mann Overarching: Once Up the Country of Ujamaa: Roll Away der Rock and Other Essays is available online and through at least 19 Libraries in North America.

RELATED

Photo of Patti and Sakura Koné and me by Diego Cortez in the Sanctuary of the former United Methodist Church in New Orleans’ Central City, April 2010. He and I were working to turn the abandoned Church into a Digital Arts and Training Center for the neighborhood. Patti immediately dug from one pocket and contributed what she called “a clump of cash.” She later added my first post about ‘The B.P. Oil-Spill’ to the Souvenance part of her website.

The 'BP Oil Spill' Was a Made-It-Happen-On-Purpose (MIHOP) Disaster: Fight the Blob, Part I

BILL JABLONKSI, founder and editor of the spectacularly informational Puppetgov.com and a brilliant maker of Videos, too, and I collaborated on pieces between 2008 and 2012. Working with Bill was a great pleasure.