Appreciating Jack and his Pic and the Beats

In 1971 I reviewed Jack Kerouac's 'last novel', Pic, for Rolling Stone. A larger Appreciation is published here, along with pages from David Amram, Matt Gonzalez, and April Smith--friends connecting.

The banner is another graphic gathering from the Long Arms of Honus Paige…. Two of my favorite baseball-players, Honus Wagner and Satchel Paige, united in name.

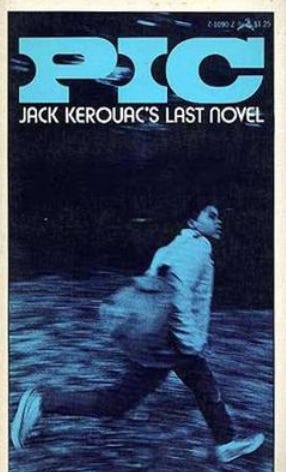

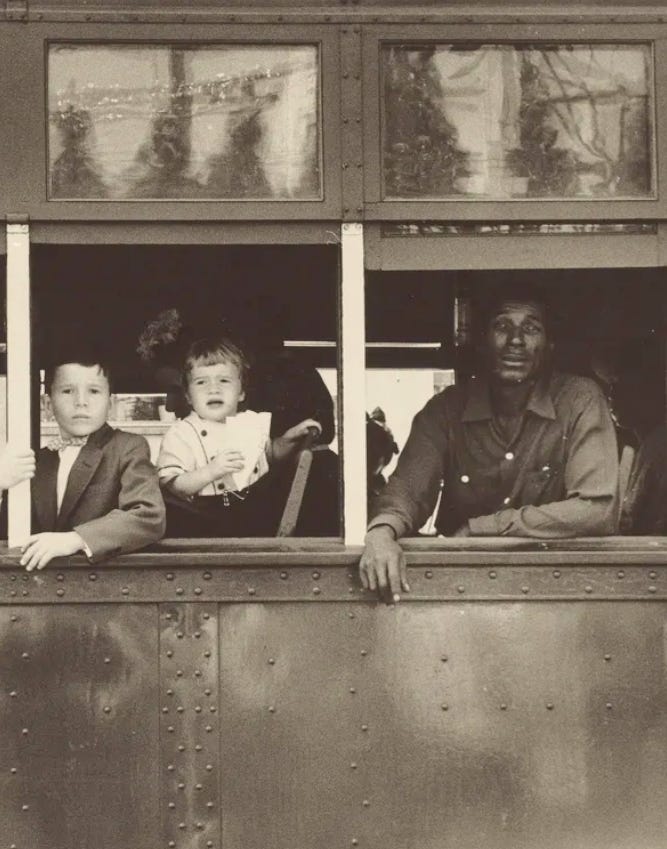

Above you see a large detail from one photo in Robert Frank’s book The Americans, ‘Trolley’, caught in New Orleans, 1955; you see the 1971 front-cover of Jack Kerouac’s ‘last novel’, Pic with a representation of the imagined 10-year-old Pictorial Review Jackson in full stride; and you see Jack agape. Each image is to me very vivid and deep and together they’re like Jack’s writing in combining the everyday and ecstatic.

In 1971, when we were both 20, a good friend from Stanford’s Creative Writing Class, Michael Rogers, passed along to me the opportunity to review Pic for Rolling Stone. About 25 years the later the magazine asked to include the review in its book about the Beats and I wrote an expanded appreciation.

I hope that you dig it. Then—52 years ago!—and now, Jack was like a friend and guide and warm voice of possibilities. He was with me from age 16 onward, painting pictures—depicting characters, and tenderly evoking an ‘America’ that we wanted to love across all bands and dials.

After the review, we’ll also connect here, middle of this Holidays’ season, to friends who themselves connect in my admiration for them—David Amram, Matt Gonzalez, and April Smih.

And now to Jack and his Pic and the Beats.

JACK KEROUAC’S

PIC

Novel from Grove Press, Zebra Books, 1971

Jack Kerouac’s last novel is one of his least autobiographical and most imaginative books of prose as well as one of his shortest and slightest.

Pic is a pretty pleasurable l’il ol’ book.

It’s another of what Jack called his ‘picaresque narratives.’ Its narrator, Pictorial Review Jackson, is a 10-year-old black boy. Using dialect and exclamations--with many an I-tell-you and dog-my-cats and Whool!--and with important proper nouns accentuated through CAPITAL LETTERS--young Jackson tells about his stay-at-home times in rural North Carolina and then his adventures on the road by bus to New York City: in New York City: and on the road by thumb and bus to California.

Pic is like the grown-up boys in Jack Kerouac’s more famous books, his excitable wonder seeking high experience and finding lyrical phrases for it. Like Dean Moriarty, Pic is an exaggeration, a super-expression, born of Jack the writer’s own wishes for vibrant LIVING in the United States.

Pic stays with his grandfather in an old Carolina house. The boy’s mother is dead, his father and older brother are gone from the place. His Aunt Gastonia ‘puffs and butts by’, bringing Pic and his grandpa food. Grandfather dies despite the efforts of Mr. Otis, ’a pow’ful tall man with yaller hair, and Pic has to move in with Aunt Gastonia and Uncle Sam and their six or seven children and fearsome, blind Grandpa Jelkey.

In this cramped house Grandpa Jelkey threatens to curse Pic by touching him seven times.

Enter Slim, Pic’s older brother. Fast-talking, fast-dressing, dancing and shuffling, Slim has come to take Pic back to New York with him. Aunt Gastonia, Uncle Sam and most especially Grandpa Jelkey oppose the move. The pow’ful, yaller-haired Mr. Otis shows up--quizzes Slim-- denounces New York’s depraved ways--and decides that Pic should be placed in the safekeeping of a GOOD HOME.

Slim appears outside Pic’s window. Pic jumps to go with him. They ride the bus north. Slim talks with Whitmanesque expansiveness.

Whool! He talks of the ‘immemoriam Memories of the Gettsburg ShilohBattle of Smoky Appamatoxburg, whool.’ He talks like Dean Moriarty/Neal Cassidy and Jack’s own Railroad Earth ruminations. He talks like bebop prosody that reduces common values of the West’s to artificiality beside private and mystic/Buddhist perspective.

Slim says that the Mason-Dixon Line is ‘ “jess like all other lines, border lines, state lines, parallel 38 lines and Iron Europe Curtain lines. They’re all ‘ “jess ;imaginary lines in people’s heads and don’t have nothing to do with the ground.” ‘

New York City amazes Pic--its ‘whole heap of walls’: its ‘most p’culiar brown air’: its ‘great gang of folks.’ The boy meets Slim’s wife Shiela, who has just lost her job. Slim talks about how tired he is of being poor, how he wants to play tenor saxophone in a club, how he wants to make make people ‘ “learn how to enjoy life and do good in life and unnerstand the world.”’ In the latter set of intentions Slim, too, is like his writer.

Slim takes and loses two jobs. Cramping in his arms keeps him from shoveling any more fudge in a cookie factory. Then he’s fired from a cocktail-lounge band when the lounge’s owner deems his suit too shabby to play in front of a ‘ “pretty toney holiday crowd.” ‘

The three pack up and head for California. Shiela goes by bus, Pic and Slim start out hitchhiking. The brothers hear about the mystery of television --hear about ‘the ghost of the Susquehanna’--before they again step into the nice, warm, moving panorama of a bus. They ride all the way to Oakland--to Shiela--and to the cherry-banana ice-cream split that is Pic’s particular desire and delight.

You can see how Pic moves--fast. It misses much of what pre-Beat (and pre-Bebop) conventions require of novels. It lacks characterization in depth: careful accumulation of detail (‘Details, details, details!’, Dostoyevksy reminded himself): and evidence of time’s effect.

Pic lives most by its linguistic evocations and internal happenings. Its language is often charming and sometimes magical. See: ‘Father McGillicuddy was s’tickled he was sunrise all over.’ Feel, as Pic’s bus enters Washington, DC: ‘they was the finest, softenest wind blow in soft from the river, and make ever’ thing ripple and jump in the water, most peaceful.’ Hear, as Slim plays in the lounge: ‘he was pushin’ the horn to go ever’ old way zippin’ here and ‘zoopin there, he then all-drawed-out himself on one breath way high up, and threw it way down ‘BAWP’ and back again in the middle, and the drummer-man looked up from his crashing sticks, and yelled “Go Slim!” jess like that.’

Through Pic the narrator, Jack writes with the expressive abandon that was his own aesthetic. He wants to vivify both immediate and meditative sensations. His gift for conveying feeling is like that of other Romantics born in these States: he’s like Whitman, Mark Twain, Fitzgerald, Faulkner, Miles Davis, and many more.

También, Jack Kerouac’s books want realization of the potential for colorful purity—meaning mixed-race purity—that’s always struggled to liberate the concept of ‘America’ and this society’s literature.

In 1957 big media--TIME / LIFE etc.--named Jack ‘King of the Beats.’

Now, the Beats were and are America’s great post-Bomb turn toward personal liberation. Seeking an alternative to The Air-Conditioned Nightmare that Henry Miller described one decade before them, they hark back to New England’s Transcendentalists one century earlier.

They look outside White America’s advertised Destiny for models. They look to Indians in both Hemispheres, to Buddhists, and even to fellaheen guerrilla. They refuse submission to Steamboats and Railroads and Interstates and transistors. They stand against Corporate conformity and Harvard canons. When asked to explain his poetry, circa 1958, Gregory Corso answered: “Fried shoes!”

And yet--sad irony!--irony gigantic as that of ‘America’!--the marketing campaign for Beats was and is the great advertised rebellion for Western youth, as well as it is the great post-Bomb distraction for Western bohemia. Now as in 1957, the Beats offer a diversionfrom people’s struggles for national liberation in the Southern Hemisphere.

Still, we can be glad for this last novel from Jack Kerouac. We can be glad at his marvelous sympathy and musicality—his love of people and their differences and any instance of generous vitality—while we can also recognize the melancholy that inevitably tinges his own vigor—as America’s promises remain undelivered, its motley of French Canuck and Southern Black and who-knows-what-else far from fairly and justly embraced.

The whole of Jack’s books make a tape of his passage through 30 or so years--the Duluoz Legend. A few of his finest books are most introspective and lesser-known--Big Sur and Desolation Angels. The best of his prose rolls and sings with poetic evocation, easy on the ear as inspired free-form radio. ‘Long page of oceanic Kerouac is sometimes as sublime as an epic line,’ wrote his friend and main publicist Allen Ginsberg. There are also the multiple, musical facets of Jack’s outright poetry, such as can be found in the 242 choruses of Mexico City Blues.

Through Jack we can smell asphalt tarry and bygone. We can step into Cafeterias now razed and replaced and see pensioners with their cuffs frayed and arms steepled above their cups.

We can know the Beats, those tender aliens who answered rockets and Wardens with dreams of a nation that might open up to accord with their own wild, Romantic, deprived and seeking hearts.

Below is the full photo, ‘Trolley’, shot by Robert Frank in New Orleans, 1955, and included in his indelible book The Amereicans, along with my tinting of the metal and the rivets.

More from and about David Amram, Matt Gonzalez, and April Smith

David

In 1959 Robert Frank and Alfred Leslie co-directed the short, improvisational movie Pull My Daisy. David Amram wrote a soundtrack of Dolphyesque intervals. Its opening song, “Pull My Daisy”, with Jack’s whimsical, visionary verse, is literally fabulous. And the voicing by Anita Ellis is superlative, too.

David remembered Jack for a Concert of ‘Classical’ and ‘Jazz’ music that was a main part of the ‘Village Trip’ two weeks in Greenwich Village. ‘Jack’s favorite composer was Bach, …”

Such a breadth of heights that David makes out remains the ‘America’ belonging to all of us,

David’s home-page.

David in Clearwater, Florida.

David’s second Hour of Interview with Musis from Maryse’s and my Spiritual as Music series.

Matt Gonzalez, Collage-Artist and Essayist and 2003 insurgent candidate for Mayor of San Francisco.

Matt wrtoe the Foreword to my 2002 collection of poems and songs and journalism, Flares. Flares printed the expanded review of Jack and Pic and the Beats along with Appreciations of Glenn Spearman, Ché Guevara, Seth Tobocman, Terbo Ted, Bob Holman, Distance-Runners, …

Matt has created a series of brilliant collages that the Dolby Chadwick Gallery in San Francisco displays.

April Smith is the novelist who took the photo that Matt presents on his page about the Foreword to Flares. April was an intent photographer when she and I and Michael and Chuck Kinder, Scott Turow, Tom Zigal, Ann West, Fred Pfiel, Hunt Hawkins, … were among that 1971-72 Creative Writing Class of Fellows and Graduate Students at Stanford with teachers Richard Scowkroft and Tillie Olsen,

November 1971, Palo Alto Post Office, photo by April Smith. My preferred image then was with a pack of Winstons in the breast-pocket of a $1.99 J.C. Penney’s T-shirt.

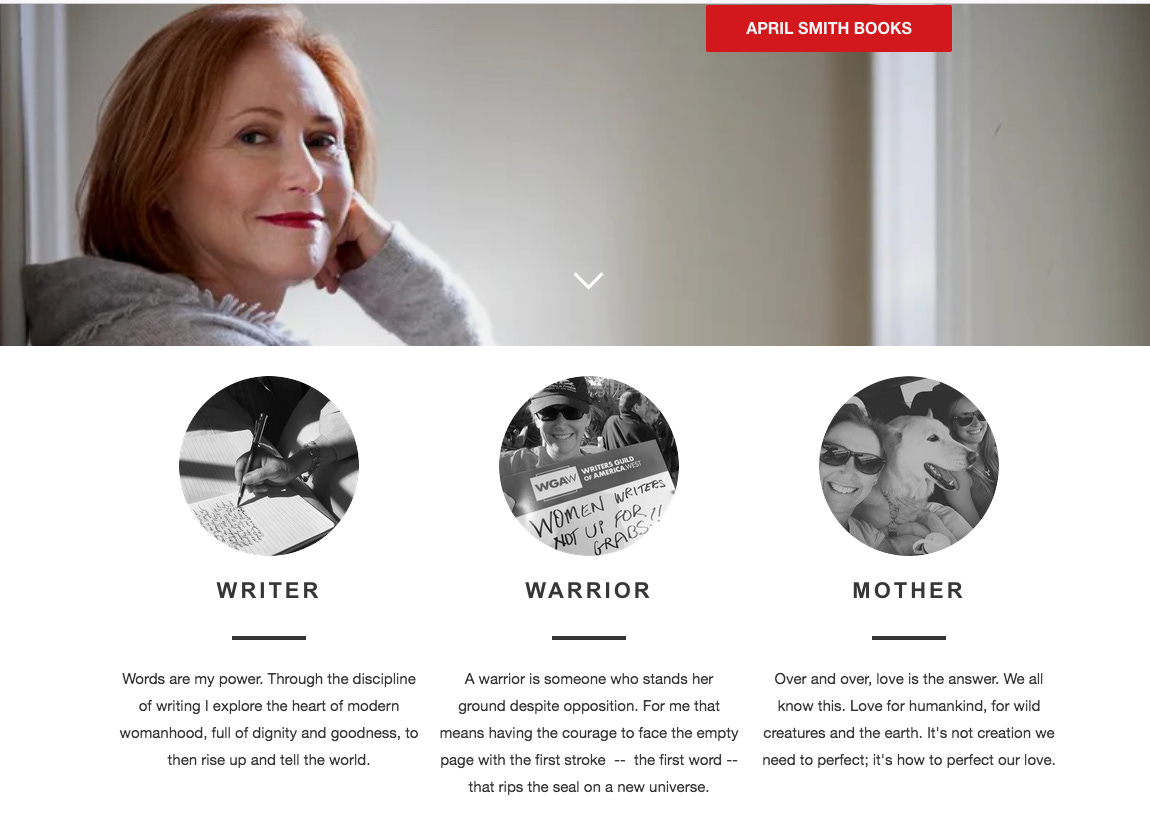

April has published seven novels with Knopf since 1994.

You may see from her website’s homepage the perspectives and values that April champions.

I admire her efforts! Here’s my review in 2017 of April’s two most recent novels.

‘April Smith is addressing America with her novels.

April Smith speaks in her fiction to the America of the United States, the Americas of the Western Hemisphere, and to our ‘American Century’ that began with World War One.

April Smith has written seven novels. Her two most recent are Home Sweet Home, 2017, and A Star for Mrs. Blake, 2014. Both of these novels derive from historical episodes that were once headlines in local newspapers and that are now obscure. Their time-spans range from 1918 (as U.S. soldiers are slaughtered by the tens of thousands in the Meuse-Argonne Offensive during the Allies’ ‘Grand Offensive’ in … Mrs. Blake) to the 1990s (as a ceremony blows up a former Minuteman-missile silo. bequeathing more than 4000 acres of South Dakota ranchland for ‘a wildlife sanctuary’. in Home).

The two novels' main protagonists are women—Cora Blake in A Star ..., Betsy Kusek and her daughter Jo in Home --and their prevailing voices and perspectives are women’s.

The two novels’ depictions of the decades that they explore thus become a gently subversive counter-narrative to dominant History. That is, their views owe to consciousness that comes from a womb, however sharp their protagonists' minds. They're mystic with Nature like novels by Willa Cather and Virginia Woolf.

April Smith's ambitions with both novels show in the acuity of her prose. She takes care to render scenes with precise vigor…. ‘

Thank YOU, readers on Substack and elsewhere, this December 23, 2023!

Just seeing this, KLACT B. Thanks! DAVID AMRAM relates that JACK and other 'Beats' especially dug LANGSTON HUGHES and Langston's readings in NYC during the 1950s.

Pic is my favorite Jack Kerouac book.